Just like that, we were out. More than three years after the country had voted for it, Brexit had got done (sort of). It hadn’t taken much. The traditional British political landscape was in tatters. Breaking news had truly broken the news. And the public lexicon had been ram-rodded with some of the most awkwardly arcane terms of Parliamentary process. On 31 January 2020 we were out of the European Union, and with barely a whimper.

Boris Johnson and his merry band of assorted gammon (some Fortnum & Mason, others Asda’s own brand) had achieved what at times seemed to be the impossible; to dissolve the UK’s marriage with the European Union. Britain was left like a battered set of buttocks in a pulp political thriller written by E L James. The divorce was agreed, and all that remained was an awkward year-long polyamorous open relationship while the UK and its European counterparts attempted to unpick nearly 50 years of intensely close trading arrangements (and divvy up the good crockery).

Now, the beleaguered British people had been freed up to worry about other things, such as remembering the name of the latest storm that was busy knocking over their garden fence. Obsessing over the fact that January and February appeared to last a decade (and 2020 was a Leap Year, God help us). And more pressingly, how long our stockpile of toilet toll and dried pasta was going to last in the Coronavirus lockdown, which in turn, had made Brexit appear rather like a trivial bout of man flu.

While the Brexit saga unfurled, I set out on a journey to the places that did and did not vote to leave the EU. I went to some of the most extreme Leave strongholds and the most ardent Remain redoubts. All were at the end of a railway line, or held some other full stop on a transport route. Although such a metaphoric mise en scène may have gradually run out of steam, this journey revealed to me a shrinking Kingdom carved up not solely by Leave and Remain, but by the winners and losers of decades of uneven prosperity. Is Brexit a bright new future that will even up the odds, or the end of the line?

A steaming bowl of Brexit

On 23 June, 2016, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland stared into the abyss. By 24 June, 2016, it had flung itself head first in. Overnight, the British people had opted to finish with the European Union by text; ‘Soz, it’s you not me.’ Not only was Brexit the most seismic political event to hit 21st Century Britain, it could also easily double up as a breakfast cereal brand. ‘I start every morning with a bowl of Brexit and a steaming mug of Parliamentary Prorogation’.

As I set out to the Leave and Remain hotspots throughout the United Kingdom, I went through a break up of my own. My girlfriend and I took part in a two person referendum with the question on the ballot; “Should INSERT NAME remain a member of this four year relationship, or leave this relationship?” Unlike the real EU Referendum, we had a 100% Leave vote and the deed was done, without an act of Parliament in sight.

Although I initially appreciated being able to make my own laws and enjoyed the new-found control over my borders (via a series of Air BNBs, hotels and a month spent in a friend’s spare room while waiting for a permanent place to live), it wasn’t all fun and games. Breaking up with a long-term partner is like peeling apart two bits of Velcro; while some might just want to rip them asunder in one glorifying motion, I instead set about gradually unplucking the bonded fibres, breaking the ties that bound, until previously separate lives could be resumed.

Effectively, it’s like working your way at a torturously slow pace, at great expense and through often bottomless emotional torment on a journey that only gets you back to square one. And all that time you can enjoy hours spent forensically picking over what went wrong, why the love had gone and where to place the Northern Ireland customs border. Oh wait, that might be Brexit…

Big Dave’s European vacation

The EU Referendum of 2016 was not actually new. A preceding vote on leaving the European Economic Community (EEC) was held under Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, in 1975, just two years after we had joined. That vote came out at 67.2% to 32.8% in favour of staying in Europe. However, the seed was planted of being better off alone. Over the next 50 years it would fester inside the Conservative party like a benign tumour. Even Margaret Thatcher – the Iron Lady who famously said, “No, No, No”, in 1988 to Brussels expansionism – ultimately fell into the yawning chasm within her party over Europe.

More than 40 years after the original vote, the tumour finally became cancerous. To some, the decision to leave the European Union was a coup de ’tat by the crazies, intent on isolating the country from years of prosperity, progression and peace in Europe. For others, it was a confirmation of a long-held view that the EU was a bureaucratic mill-stone that the UK could do without. However, just like Jaws isn’t just a movie about a shark, the EU Referendum wasn’t just a vote about Britain’s membership of the EU. Rather, it scratched a deep itch within the country – and more notably the conservative movement – that had rapidly grown agitated and sore. And it was a gamble for one man that hadn’t quite paid off.

Aware of the bristling European malaise in his party, along with the rise of the UK Independence Party, the then prime minster David Cameron had proposed a renegotiating of the UK’s relationship with the Europe Union. Effectively, some pretty darn tough marriage counselling, I’ll have you please. Cameron wanted Britain to be effectively allowed to opt out of the EU’s core ambition of forging an ‘ever closer union’ between the people of Europe. In sum, we don’t want to sing ‘Kum ba yah’ with you at the Brussels camp fire anymore. However, that was akin to going into a negotiation about the terms of membership to a golf club on the basis that golf isn’t actually a game.

With a pungent whiff of Neville Chamberlain, Cameron emerged in February 2016 from the talks proudly waving his deal. And he had that 2015 election victory in his back pocket, with his new ‘odd couple’ sitcom with Nick Clegg fully commissioned for proper telly.

What his final proposed deal with the EU eventually said is worth quoting: “It is recognised that the United Kingdom, in the light of the specific situation it has under the Treaties, is not committed to further political integration into the European Union. The substance of this will be incorporated into the Treaties at the time of their next revision in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Treaties and the respective constitutional requirements of the Member States, so as to make it clear that the references to ever closer union do not apply to the United Kingdom.”

So, we’re in but also not in and that makes sense ‘cos we say it does, OK? The in-out-shake-it-all-about deal was supposed to be turned into legislation by the European Commission after the UK voted to remain in the EU in the referendum. With that sealed, Cameron no doubt went straight down Ladbrokes with what was left in the Budget.

The prime minister must have taken heart from the Scottish Referendum. That brutal slug fest had been covered with about as much balance in England as William Wallace’s big day out in the capital on 23 August, 1305. The undercurrent bristled with, ‘These heathens will see sense eventually’, by the pink-cheeked toffs that are forever in power to some degree. But then, of course, the Scots stayed. With a Thanos-like click of his fingers, Cameron had kicked off the EU Referendum. Was he confident? Is a highly privileged white man ever not confident? It’s like entering a competition when you not only have rigged the game, but could change the rules at any minute if things appear a bit dicey. Or not, it seems, when equally privileged and powerful men have got there first.

So, the country steamed ahead with the vote. For whatever reason, those who spearheaded the Vote Remain campaign spectacularly misread their opponent’s ability to leverage the dark arts of electioneering. Dirty money, a full court press on social media, psychological manipulation, foreign interference and downright fraud are all alleged. You’ll find better accounts of the ins and outs of those sordid stories elsewhere, with considerable fewer bad puns.

Whether he was too busy wondering if Barack Obama was going to respond to that wink smilie text message, Cameron misunderstood the feeling in many parts of the four nations that make up the United Kingdom. So, one of the most depressing pageants in British democratic history (and that, most definitely, is saying something) proceeded ahead. And (almost) half the country ended up in the early morning, staring in disbelief at the result:

Vote Leave: 51.89%, Vote Remain: 48.11%.

Although the turnout of 72.2% of the electorate was higher than most General Elections, the Vote Leave win was hardly what you’d call a majority. If this was an actual race, it won purely by having an overly large nose on the dip to the finishing line. But the die was cast, the pieces were moving and the UK was on the road to single-dom (is there a country version of Tinder? Just asking for a friend). Leave voters were in raptures, Remain in tatters. But this was no Magnus Opus of electioneering. It was the political equivalent of a muddy non-league game, in which 22 players kick lumps out of each other until the ball ends up somehow in the net. It’s not an own goal. No one even knows what it is.

I was in the 48.11%. I shared many people’s incredulous disbelief as to why someone, anyone, could regard an A-Team of Michael Gove, Boris Johnson, Nigel Farage and Liam Fox as being gatekeepers to a credible plan for their future. But I, along with all the other ‘Remoaners’ as soon become a tedious insult, were in the minority (just). The nation, it seemed, had spoken and the will of the people (well, again, just over half of them) was to leave the European Union.

Whatever side they chose, most people who voted in the referendum had, in all likeliness, hardly ever thought about the EU up to that point. Perhaps the occasional eye-roll and head shake at some tabloid story about a ‘health and safety gone mad’ style ruling. Maybe some guy in the pub droning on about straight bananas and how Turkey was going to join the EU and the price of kebabs would go up. It is doubtful, though, that many people spent their evenings debating the vagaries of Brussels’ working directives over the dinner table.

But now, a choice had been placed on the table. A question: “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?” How is a normal, rational person going to approach such a nebulous question? Are they going to spend hours boning up on European law and institutions? Or travel to Brussels to perform a rudimentary inspection of the institutions and their respective policies on fruit curvature? No, because it is boring. Rather, they will read the question as, are you happy? Do you feel prosperous? Do you feel safe? Do you feel heard? If the answer is no to some, or all, of those questions, then why vote for the status quo? At that time Vote Leave planted a powerful seed; let’s take our country back. Let’s get back what we’ve lost. Let’s take back control.

OK, we got very affordable Polish builders out of the EU but what else has it done for us? We ruled the waves before, we can do it again. We can charm the world with our plucky spirit, and return home from our voyages with chests laden with gold to share out among everyone in the four nations (Disclaimer: Some exceptions may apply). We’ve got the ‘special relationship’ after all. And if ‘The Donald’ wins the White House, he loves Brexit!

I mean, come on. We survived the Blitz, didn’t we? Ah yes, the ‘Blitz spirit’. Amongst the chest thumping it’s rarely noted that the Blitz was survived at a cost of 32,000 lives and with around 60% of London homes destroyed by the bombing. Or that there was rampant crime, with 1,662 cases of looting coming before London courts in one month alone in October 1940. But yeah, Blitz spirit it is then…

Even the most ardent Brexiteers would struggle to argue that what ensued following the 2016 vote represented taking back control in any meaningful way. Our political class appeared to be unfit to run a school tuck shop, let alone one of the largest economies in the world. Cameron quickly cleared off like he had just booted a football through a neighbour’s window and then nonchalantly wandered off with a “dum di dum dum”. And then Theresa May sashayed robotically into the hot seat, chanting ‘Brexit means Brexit’ like she was playing a game of political Kabaddi. She no doubt hoped that no one would remember she had in fact backed Remain. All was missing from her leadership pitch was an Alan Patridge-like, ‘Can I just shock you?’, before downing a glass of Blue Nun wine.

After becoming leader, Mrs May set out to successfully score a colossal own goal with a disastrous 2017 general election that lost her government its majority and instead shackled her future to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) of Northern Ireland. Yep, the same Northern Ireland that has the United Kingdom’s main land border with the European Union. Undeterred, Mrs May set out to lead a Team Brexit initiative with about as much efficiency, coordination, progress and harmony as an early round on The Apprentice. Her Brexit strategy appeared to be akin to a removals company trying to get a sofa into the house that everyone knows is never, ever going to fit.

The other nations of the European Union must have looked upon Britain like a distant friend going through a mid-life crisis. We just needed to buy a leather jacket and a mid-range sports car, and snag a young girlfriend who was definitely into us, and the picture would be complete. And for the watching public, rarely had a political event left them so angry, fascinated, puzzled and crushingly bored all at the same time.

This calamitous pantomime possibly reached its nadir when Chris Grayling – the then transport secretary who appeared to be the political equivalent of Mr Bean and had his own #failinggrayling hashtag online – awarded a £13.8m government contract to provide extra ferry services between Ramsgate and Ostend in the event of a devastating ‘no-deal’ Brexit scenario to a company that has never run a ferry service and didn’t own a single ship. If that wasn’t enough, it emerged that Seaborne Freight had re-used the terms and conditions from a takeaway food outlet, advising travellers to check their goods before “agreeing to pay for any meal/order”. The company also misspelled the address of its own head office in its Companies House filing. Seriously, what would even count as satire anymore?

Eventually, what seemed inevitable came to fruition. Theresa May finally released her white knuckle grip on the Number 10 door knob, and via a rather ludicrously one-sided Conservative leadership contest, Boris Johnson was named prime minister. Not by the 45,000,000-strong UK electorate, but by 180,000 Conservative Party members. (Yep, sounds about right.) Despite a stuttering start in which he lost more votes than he has children (probably), Johnson would eventually take the leftover curry that was Theresa May’s Withdrawal Agreement Bill, pick a bit of stuff out, put a bit of stuff in, shift the naan bread into the Irish sea and then reheat the whole meal until it was to the satisfaction of the now exhausted and famished European team.

The deal had previously been destroyed by MPs like it was an overweight Sunday football team getting chucked into the Premiership. But Johnson had won a majority at the December 2019 general election so thunderous that he could have shot someone on Fifth Avenue and.. oh wait, sorry, wrong blonde demagogue. On 23 January 2020 the rehashed deal sailed through Parliament like a British clipper cutting through the West Indian sea. Just when Jeremy Corbyn’s red revolution had appeared ready to roll, the Empire had struck back.

On 31 January, 2020, a damp, grey and rather miserable day was capped at 11pm, when the Withdrawal Agreement came into force and the UK was officially out of the EU. Some people had greeted each other with a ‘Merry Brexit’ or ‘Happy Brexit’ earlier in the day, like this was a second stab at Christmas when all your presents were Ladybird books on, ‘How to plan for armageddon’. Newspapers splashed their front pages with lurid Brexit Day collages. Boris Johnson hailed the “dawn of the new era”. In the European parliament, MEPs sang ‘auld lang syne’, while Brexiters, led by Nigel Farage and Anne Widdicombe, waved tiny Union Jack flags like they were celebrating a Royal divorce.

Ahead of the big day, there had been a row over whether Big Ben, then being renovated, should be lifted from its slumber to ‘bong for Brexit’. That was a followed by an equally important debate over the use of an Oxford Comma on the Brexit 50p. Yes, it was a typically underwhelming apocalypse; how very British of us.

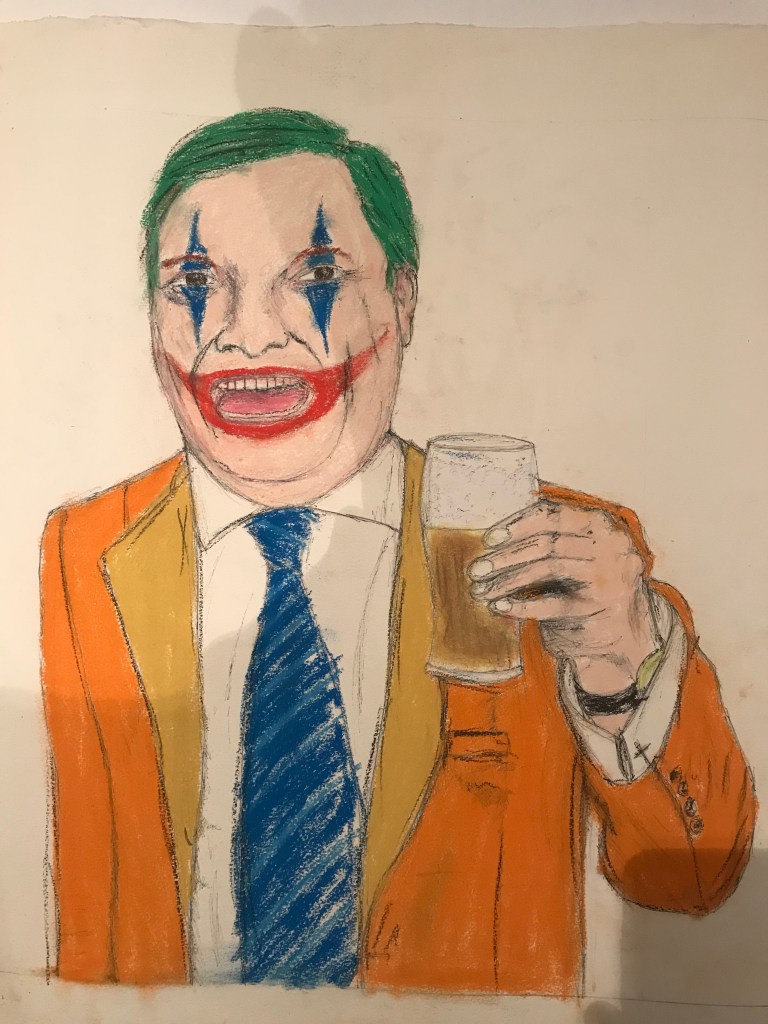

Ultimately, Big Ben didn’t bong for real, rather it was simulated on the frontage of Downing Street after a digital clock had ticked down. Its crescendo was met with great jubilation on Parliament Square as Farage – who had earlier unveiled a portrait of himself entitled ‘Mr Brexit’, in an event hosted by Jim Davidson – led the celebrations. In a febrile atmosphere, Brexiteers sang God Save the Queen while waving more Union Jack flags. The victors enjoyed the spoils, but all Remainers heard as Big Ben’s Bongs digitally rang out was, ‘bring out your dead’.

The following day, 1 February 2020, I flew to Amsterdam on a short break with my new girlfriend (spoiler alert: I found love again). I watched as British people looked confusingly at the passport queues. ‘It still says ‘European Union’ on mine,’ a man said to his travelling companion, peering at his passport.

‘Fuck it, I am just gonna go through this one,’ he added, before heading through the EU passports gate, as the bewildered border guard gave a weary sigh.

The end of the line

The travel writer Bill Bryson once wrote in his classic British travelogue, ‘Notes from a Small Island’, that the Brits are the happiest people in the world largely because our joy is so modest and achievable. A pint after work, a cup of tea and a biscuit, a scone with jam and cream (let’s not get into the ongoing, bloody war over which goes on top of which). Such twee sentiment feels good to cling onto, but the truth is that at the time of the EU Referendum people were, for various and complex reasons, angry. In some cases, very angry. And all the tea and biscuits in the world wasn’t going to change that.

Just as in the final throws of a dying relationship, it is tempting to try to roll back the clock and cling to what has ultimately been lost. If you were so minded, it would be easy to hold the belief that Brexit could be stopped, reversed, and the UK returned to how it was. Just like an old flame could be rekindled from the ash that remained. But that is just as deluded as trying to ‘take back control’. And then like ratcheting through the stages of grief, come the recriminations. It’s easy to throw your hands in the air and decry those with an opposing view. To damn them as racists and bigots. Despite the closeness of the vote, 17,410,742 million people voted to leave the European Union and a group that big can’t be dismissed so easily. They are normal people. They’re concerned about their lives, their livelihoods and their futures. If more than half the United Kingdom wanted to ‘take the country back’, what is that country?

The End of the Line is the story of Brexit told in the places that did and did not vote for it. In this series, I set out on a journey to the final stop at transport lines across the British Isles, and beyond. I visit Brexit strongholds, including coastal towns, historic locations and important ports; and Remain redoubts, including seaside cities, London boroughs and a British outpost in Europe. Each place has a different story to tell in the context of the vote. There is something about being at the end of a line. It’s a feeling of having nowhere else to go. These locations either feel energised, exciting and engaged, or barren, bleak and forgotten. They’re either a desirable destination, or a dead end.

The End of the Line is not an overarching political history of how the vote to leave the European Union unfurled. Nor is it an extensive repository of interviews with those who voted on either side of the spectrum, giving their opinions on the whys, what’s and wherefores. You can find better sources for both streams of thought elsewhere. Rather, this work is about the social and economic history of the places that voted in or out, and what that tells us about the state of the nation now, and in the future. And most importantly this is a journey to try and find out what it means to be British in the age of Brexit. Last stop, all change.

Next up, the first stop on our journey in Brighton & Hove.