The End of the Line is a 10-part travelogue journey to some of the highest Remain and Leave areas in the United Kingdom’s 2016 Referendum on EU membership. It was written over two years from 2018 to 2020, before Coronavirus made Brexit seem like a spot of man flu.

Lambeth voted 78.6% Remain in the EU Referendum

Originally written in January 2019

When I was growing up in Yorkshire, London was known as ‘that London’. It was a place far removed from ‘our England’. In my young eyes, London was an exotic, intimidating beast of a place. Occasionally, you’d hear of someone going there on a school trip, or having a holiday seeing family or friends. It was always deeply impressive, as though they had been selected to go into space. When my Dad moved to Essex in the mid-1990s, I used to travel down to London to meet up with him, returning to Sheffield within the same day. Each time that sense of mystery about the capital faded a little more. Samuel Johnson once wrote, ‘When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life.’ But he’d clearly never done a day trip from Sheffield to London St Pancras, and back again, once a month like a human yo-yo.

Now, I work in London, commuting up from Brighton. The English capital has become part of my life, but Johnson was right, in part; I still get the occasional thrill from walking around the city. You never do lose the buzz. It’s not just the world-famous landmarks, but also the seedy swing of Soho, the dizzying wealth of Mayfair and the edginess of Camden. Even the corporate bleakness of Canary Wharf has something about it, especially when thousands of lights twinkle in shiny ripples on the water at night.

London has never been the sum of its parts. Instead, the parts are the sum of London. The 32 individual London boroughs make the city among the most vibrant, diverse and dynamic capitals on Earth. Regardless of the talk of politicians about creating ‘northern powerhouses’ and strong devolved nations, London will always remain the true powerhouse of the United Kingdom. It is the beating financial heart on the four nations, pulsing out its waves of prosperity that reach as far as the uneven winds prevail.

OK, Brixton isn’t technically at the end of the rail line. But it is at the end of the Victoria line on the Underground, commonly known as the Tube. In the context of Brexit, this doesn’t seem a meaningful stretch of the rules. Opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 7 March 1969 (for some reason Queen Victoria was unavailable), the Victoria line is the second youngest Tube line, after the Jubilee line (it will be the third youngest when the Elizabeth line opens). The Metropolitan Railway, now just the Metropolitan line, was the world’s first underground railway when it began operations all the way back in 1863. The subsequent Tube lines that were added all have their story to tell. Tthe Bakerloo line, opened in 1906, was supposedly created because some wealthy men had complained that they couldn’t get to Lord’s Cricket Ground fast enough.

Before getting to the Underground at Victoria, you first have to navigate the Victoria station concourse. I spend more time here than I would care to admit; a good portion of which is devoted to staring up at the information boards wondering if Southern Rail would ever achieve the feat of a train arriving on time. The concourse is a space so huge yet also so cluttered that you end up traversing it in a dreary game of human Frogger. I really hate this place.

In the centre of the station is a large Weatherspoons pub. I recall sitting here in July 2018 on the day of a protest march against United States President Donald Trump’s visit to Britain. Amongst the harassed-looking commuters were people dressed in bright colours, bearing placards with various protest epithets, many warning that pussies would bite back if grabbed. I had been working that day but my girlfriend (again, still in post at the time) and her friend had gone to the protest. One of their placards said of ‘the Donald’, ‘I’d call him a c*nt but he lacks warmth and depth.’ You have to be proud of that a slogan, although a swear word of such magnitude probably limited the media coverage.

We sat drinking cheap Weatherspoons beer as two young people sat down near us. They were wiry and androgynous, with shaved heads and piercings. The kind of people you’d call ‘alternative types’, if you were a bit of a c*nt. A man whose combined mass probably covered both of them clocked the duo. I observed him as he itched and twitched to say something, until he leant over and guffawed across the tables, ‘so, what’s wrong with Trump, then?’.

I had noticed him earlier, bedecked in a Help for Heroes t-shirt, espousing to the bored bartender that Boris Johnson was ‘definitely a shoe-in after May’s gone’ (to be fair, an ultimately prescient political prediction). The two young people on the terrace outside just ignored him. He persisted a couple of times, until someone pointed out that a grown man heckling two people not even half his size wasn’t exactly a good look, even in a Weatherspoons. Eventually, he gave up, no doubt convinced that he had put these ‘alternative types’ in their place.

Donald Trump and Boris Johnson; How do they connect with this guy? How does a serial draft-dodging demagogue, who appears to provide exactly zero help to any actual heroes, speak to this man on such a fundamental level? Equally, why does a floppy haired old Etonian, who should he meet this man would probably presume that he was there to fix something, resonate so strongly with him? It makes no sense and absolute sense at the same time.

On a Saturday in January 2019 I head across the station forecourt, dodging the rabbles of confused tourists and herds of school trippers. London Victoria is very much an improvement work in progress. It had been undergoing a major redevelopment that was apparently due to end in 2018, but in 2019 most of the station still looked like that back room you promised to redecorate but, you know, stuff kinda got in the way. Exiting the concourse I plunge down the stairs and prepare to spelunk deep underground.

I take the Victoria Line every day to work, but in the opposite direction from Brixton. I could easily have selected Walthamstow, the other end of the Victoria line, for this trip. The borough of Waltham Forest voted 59.1% to remain in the EU. In fact, the majority of London voted to remain in the EU. Across all 32 London Boroughs, 59.9% (2.26 million voters) plumped in favour of staying in Europe. Barking and Dagenham, Bexley, Sutton, Havering and Hillingdon were the only areas to support leaving. In some boroughs, the vote was more than 70%, with the highest being Lambeth, at 78.6% Remain and where Brixton is located.

Although the borough voted unequivocally to leave the European Union, such a view was not shared by all of its elected MPs at the time of my visit. While Chuka Umana (Streatham) and Helen Hayes (Dulwich and West Norwood) voted to Remain, one of the most prominent vote Leave advocates was Kate Hoey MP (Vauxhall). Hoey had consistently voted against greater EU integration and she joined the rather disastrous 200-mile ‘Leave Means Leave’ march from Sunderland to London, alongside Nigel Farage and fellow Brexiteer Andrea Jenkyns MP.

I walk down the escalator (stand on the right, walk on the left is the Tube mantra to remember for novices) and head into the bowls of London. A network of almost 250 miles of Tube lines criss-cross underneath the Capital, ferrying people various distances. The longest run between two Tube stops is 6.3km between Chesham and Chalfont & Latimer on the Metropolitan line. The shortest is Leicester Square to Covent Garden on the Piccadilly line; just 300 yards, or £15,000 in a pedi-cab.

Standing on the Tube platform, I think about how perilously close the traveller is to so many different ways to die down here. Heaves of people jostle for space just inches from exposed live rails. Some stare absent-mindedly at smartphones as trains speed past at rapid rates. And the level of gung-ho adventurism of some travellers is quite remarkable. I once observed a woman jam open the closing doors of a train with a pram that actually had her baby still in it. The driver gave her a piece of his mind when the train set off.

Yet with all that, there is just one fatal accident for every 300 million journeys on the London Underground. That is truly remarkable when you think about it and a testament to those who work for Transport for London. Some of the most effective human safeguarding comes in the form of just three words – ‘mind the gap’. First introduced in 1969, this warning message may seem archaic on a technical level, but it is hard to now unpick it from the Tube experience.

There are underground railway systems all around the world; the New York Subway, Le Metro in Paris and the ornately-decorated Moscow subway. However, a strong argument could be made for London having the best. The Tube is the lungs of the city, the heaving, breathing network that keeps the city in locomotion. It is maddeningly dysfunctional at times, especially during industrial action, but few travellers in London could live without it.

The Victoria line train arrives and I get on. The train achieves a neat trick of appearing both new and dated at the same time. People embark, while others disembark, like a hasty exchange of fluids between train and station. The carriage is quiet, a blessed relief from the rush hour cattle trains. In fact, during the heat wave summer of 2018, some Tube lines hit temperatures at which level it would be technically unsafe to transport livestock. Further up from me two people watch videos on their smartphone without wearing headphones. The tinny hiss of whatever crap they are cackling at rings around the carriage. I think about how this should be a crime with a devastating punishment applied to offenders.

The doors slide closed like a rent-a-car Starship Enterprise and the train lurches forward. The first stop is Pimlico, home to the Tate Britain and the Conservative Party headquarters in Millbank tower. A massive student protest occurred here in 2010, with students almost occupying the building in protest to cuts to further education and the ongoing ire against eye-wateringly high tuition fees. Onwards the train goes through Vauxhall, home of the Oval Cricket ground, and into Stockwell.

Two Watford fans get off here on their way to watch their team beat Crystal Palace 2-1. A Spanish couple chats away across from me. I absent-mindedly look up and peruse the advertisements lining the carriage. ‘Christian Connections’ is a Christian dating service that had apparently been going for 20 years. I wonder how it works; maybe swipe right for salvation, left for damnation (or a hook up)? Another advert promotes the ‘Skull Shaver’, a device that looks like it came from a medieval torturer’s travel kit.

The train arrives at Brixton – all change. I follow the light herd of people as we wind down passageways lined with functionally attractive green and cream tiles. Then, I emerge, blinking from the underground and into the Saturday afternoon melee. Immediately, I hear the dulcet tones of a young man singing about the benefits of Jesus. Apparently, Christ the Saviour can heal; and yes, real illnesses, and proper diseases! He apparently had real proof of this! Rejoice everyone! Right, well, let’s disband the NHS and just put this guy on prescription with his moveable amplifier and wide-eyed, ‘maybe-don’t-come-too-close’ stare. I walk on, but make a note of his website in case I ended up getting cancer.

Brixton buzzes today. People bustle in and out of shops and pubs. White middle class kids are dressed like they have just come from a 1980s rap video. Harassed parents herd their kids down the pavement. I head off walking down Brixton Road. The rail bridge above bears an artwork created by Lambeth residents Farouk Agoro and Akil Scafe-Smith, from the Resolve Collective. It says on the side beyond the station, ‘Come in Love’, in giant letters, and on the other side, ‘Stay in Peace’.

I keep walking and pass a young man with a guitar and his face made up like Aladdin Sane era David Bowie. David Robert Jones was born in Brixton, at 40 Stansfield Rd in the area. There’s a mural to him on Tunstall Road, inspired by his pun-tastically titled 1973 album. On this day, it was almost exactly three years since Bowie had departed the Earth in 2016. It is increasingly clear that he was some sort of cosmic glue keeping the bad things at bay. Come back, space boy, we need you.

Brixton feels like it honours Bowie’s legacy; so much of it is creatively controlled chaos. Down-at-heel shops and takeaways mix with high-end boutiques. You can visibly see the battle between wealth and the soul of the area; the schism between authenticity and popularity, similar to that with which Bowie himself grappled with over his career. Brixton is an area that has changed immeasurably over the last 30 years. As with many London boroughs the influx of wealthy, middle class white people has resulted in changes that some describe as regeneration, but others would regard as gentrification. With the latter, the benefits of such a shift remain a matter of controversy and debate.

I take in the atmosphere. Over at the O2 Academy, eager fans of rock group, Enter Shakiri, are already queuing for the evening show. Roosters chicken shop had sadly bit the dust, but Morleys is still going and full of people enjoying a fried chicken lunch. I walk on a little further and see a huge mural on Stockwell Park Walk. Stretching 30ft by 40ft, it’s titled, Children At Play, and at the time one of the largest in London. It was painted in the months after the Brixton riots, aiming to show how children can see beyond prejudice and play together harmoniously regardless of colour.

By April 1981, pressure had been building in Brixton. High unemployment, poor housing, weak local amenities and oppressive police measures supposedly to tackle street crime led to significant (and understandable) tensions in the large British African Caribbean community. People were angry and that spilled over into rioting that resulted in more than 250 injuries, hundreds of vehicles being burned and more than 150 buildings being damaged. A further riot occurred in 1985 following the police shooting of Dorothy ‘Cherry’ Groce after officers had entered her house searching for her son, Michael Groce. The tensions may have dissipated but many of the grievances rightly linger to this day.

I double back and head towards the arches on Station Road. According to Brixton Buzz, Network Rail evicted traders and businesses from operating in the arches on Station Road and Atlantic Road with a view to regenerate the area. That was three years ago and not much appears to have happened since. When I visit what’s left of the Station Road market seems rather sad. There are a few stall holders but the footfall appears light for a Saturday and no stand is particularly swamped with people. You wonder, too, how much of an impact Pop Brixton has had on this market area.

Pop Brixton is a temporary project, created in partnership with Lambeth Council and due to remain on the site at the corner on Station Road until 2020. The structure is formed of stacked shipping containers, as appear to be trendy these days. It gives it a certain industrial chic. Inside is a warren of food outlets, clothing stores and swish start-up businesses. Some people walk past me remarking on how the Japanese knife shop was rather pricey. In the urban garden a woman talks loudly about an events co-ordinator job she was going for. You get the idea.

Pop Brixton is more night club than market, with afternoon revellers sitting at communal tables surrounded by neon and uncovered chipboard, drinking, eating and loudly socialising. At one end is a huge clothes shop swamped with people. The sense of retail tension hangs thickly in the air; all you’d need to do was to shout ‘50% off!’ and sheer mayhem would ensue. Numerous winding passageways are lined with food concessions. They all serve up strains of what’s loosely billed as ‘street food’. Some mash up different food genres, like Bhangra Burgers mixing burgers with Indian food, while others bring unusual and exotic cuisines. A Venezuelan food outlet offers guava glazed chicken and Venezuelan cornbread, but also a chip butty. You presume this is like an Indian restaurant also offering an omelette in case grandma can’t stand the ‘foreign stuff’.

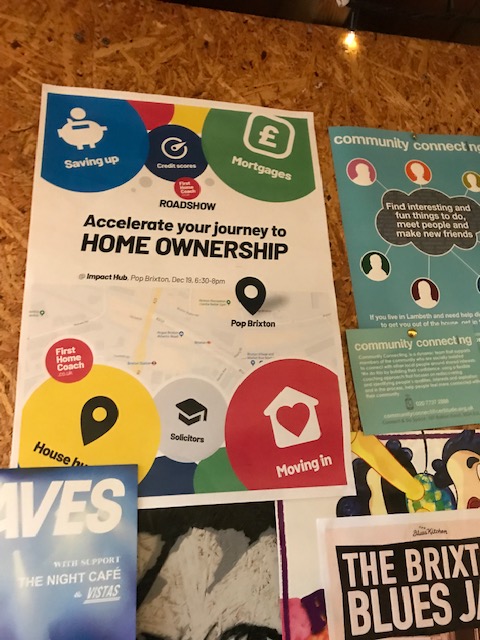

The array of choice is mind-boggling and somewhat overwhelming. I watch admiringly as people glide up to stalls and make quick choices, before heading away with paper trays loaded with goodies. It soon becomes apparent that I am the type of person to whom chip butty concessions are aimed at. Before leaving Pop Brixton I checked out the noticeboard at the bottom of the slope leading up to the upper seating area (it really is an impressive structure for a temporary venue). A poster from the Impact Hub advertises a roadshow session titled, ‘Accelerate your journey to HOME OWNERSHIP’ (their caps, not mine). Coloured circles bear topics including, ‘saving up’, ‘credit scores’, ‘mortgages’ and you’d hope eventually, ‘moving in’.

Regardless of the economic climate at any time, the property market in London is never for the under-prepared or the faint hearted. It is a scene where winners and losers are marked, and eye-watering sums of money are spirited away in a heartbeat. Some people I know moved to Brighton a few years ago and I was floored at the large house that they were able to afford. Brighton isn’t cheap and this place was substantial. ‘How could you afford it?’ I asked. ‘Sold a flat in Brixton,’ was the response. No more questions asked.

According to 2018 data from the Land Registry, the average price of a property in Brixton was £577,352. Although that is 6.1% below the London average of £615,046, it was more than double the UK national average of £243,639. Plus, it was £252,822 more than the average for the South East of England (£324,530). Just as with many boroughs in London, buying a property in Brixton is beyond the reach of the majority of people.

Figures from the Halifax indicate that the average deposit required for a first time buyer in the UK was £32,841 as of February 2019, but they’d need to find £110,656 to get on the property ladder in London. That chunk of cash would be enough to buy a home outright in the north east of England. The influx of wealth in the capital has pushed so-called ordinary people to move farther and farther out of the city. In the eyes of some, they are taking the soul of London with them.

I leave Pop Brixton and head towards Brixton Village around the corner. This covered market and shopping arcade features stalls selling produce, including several with Caribbean goods such as plantain and ackee. I walk past a butcher’s shop and got a strong and heady waft of meat. Rather than shop for their cupboard essentials, however, most people are in Brixton Village to eat. The Joint serves up BBQ and every table is full, while the Burnt Toast Café is packed with tired-looking young parents.

The Champagne + Fromage outlet is arguably the most popular on that day. Diners tuck into garlicky snails and huge cheese boards, with glasses of champagne sparkling away in the afternoon light. Conversation buzzes in the air. People spill out into the covered market passageways, sitting on stools and using every inch of space to sit, chat and eat. I silently wish them a good afternoon and double back on myself to find a Wetherspoons (yes, I know).

There are plenty of nice pubs in Brixton, but I can’t resist seeing how a Wetherspoons goes down here. As I find out, it is packed. The Beehive on Brixton Road feels like a combination of a bar on a ferry to France and a retirement home canteen; so, the classic Weatherspoons look, then. A long, quite narrow room extends before me, a forest of lacquered wood, well-worn seating and jarring pictures hanging loosely from the walls. The chattering bleeps of fruit machines bounce around the walls. Afternoon smells fill my nose; fried food, yeasty beer, flatulence, the odd whiff of ash from a returning smoker. The hubbub always feels louder in a Wetherspoons considering the chain banned music a few years ago. It also banned dogs in September 2018, regardless of whether they were reared in the UK.

So packed is the Beehive that I end up having to scrounge a stool and find a quiet spot with not much through traffic to sit down. Nearby, a waitress deliveres plates of chips, beans and fried egg to a booth. The old boy in the group gives her some lip and she smiles and gives it right back. I take a sip of my pint and pick up a copy of ‘Wetherspoons News’, the Winter 2018/19 issue. The front cover depictes a range of disembodied heads of politicians, including Theresa May, the then shadow Brexit secretary Sir Keir Starmer and former deputy prime minister Nick Clegg placed on cartoon bodies. It’s like a second-rate episode of South Park.

Mrs May is depicted smiling and on the phone, while the others appear in various states of smug agitation demanding in speech bubbles, ‘Just give us any deal … please’. The cover trails the main feature in the magazine, a Circle of Deceit. The standfirst states; ‘How the metropolitan elite tried to con the British public about the need for a ‘deal’ with the EU’. I immediately flick to those pages.

The opener states thus: ‘The elites are trying to con us. We must dispel the myth that we need a deal with the EU. We don’t. A deal is a trap to keep us in the EU, so that goods tariffs continue to weigh on shoppers – are sent to Brussels to feed the fat cats in the EU bureaucracy. WE WANT TO LEAVE AND WE WANT FREE TRADE. WE DON’T WANT A DEAL…’ (their emphasis, not mine).

A central golden circle bears a long message from Tim Martin, the Worzel Gumidge millionaire chief executive of Weatherspoons, and a leading Leave campaigner, outlining why everyone else was wrong about Brexit. It’s a rant that you could quite feasibly expect to hear from someone sat at the bar in one of his pubs, albeit with an elegant line in prose. He likens ‘Europeanism’ to a religious cult that has beguiled the ruling elite into blind faith to the ivory towers of Brussels, or something like that.

Speaking of the debate over whether Britain should join the Euro 15 years ago, Martin writes: ‘What was evident then was that the bookish tribes, with important exceptions, from the dreaming spires were far more likely to be taking in by Moonie-like cults than were the horney-handed sons of the soil, who toiled in the mundane world of factories, shops and pubs.’

Around the circle are 23 points, each a statement made about leaving the EU from a commentator or publication. Many have ripostes from Martin slapped on them like brands, such as ‘not true’, ‘nonsense’ and ‘whopper’. There is no clear indication given as to why said statements were falsehoods; just that they are. A snippet on Barclays Bank economist, Fabrice Montague, who was warning clients that the no deal option will not work, is countered with; ‘you idiot, Fabrice!’

Most of Mr Martin’s ire is reserved for mainstream news sources such as The Financial Times, Guardian and The Times, over what he believes to be overriding negative portrayals of the prospects of Brexit. Even the British Retail Consortium gets a booting over ‘nonsense sent out on Boxing Day’. Further ahead, Wetherspoon’s News presents three pro Brexit articles and three pro Remain. It rather limits the strived editorial balance, though, by providing a running commentary from Mr Martin indicating why the Leave-backing articles are right but the pro-Remain ones are codswallop. It appears to be the journalism equivalent of drawing a cock and balls on the face of a celebrity that you don’t like.

I flip to another article on how Wetherspoons had shifted away from drinks brands from EU producers and moved towards tipples from outside the bloc. You’ll have to go elsewhere for your Jagermeister and Hennessey cognac it seems, although the Swedish Kopperberg brand gets a pass as it would apparently continue to produce cider in the UK post Brexit. The article hammers home the message that rather than the UK being on the cliff edge, instead “only sunlit uplands” lie beyond our membership. And in an irrefutable bit of geographic fact-giving, it adds; “It’s important to remember that 93% of the world is outside of the EU.”

Finishing my pint I leave the soporific warm fog inside the Beehive and head out into the winter chill. I walk up Brixton Road, now even busier, towards Windrush Square. British history has always simultaneously fascinated and appalled me. It’s easy to get lost in the dramatic pomp and the elaborate circumstance; from the empire on which the sun never sets to the plucky little nation the defied Hitler. However, dig beneath the hyperbole of how Britain has punched above its weight over the years, and you soon see that so much of that has come with our boot on the neck of others. And sometimes even when someone becomes part of this country, the boot remains nonetheless.

On June 22 1948, the Empire Windrush arrived in Tilbury Docks, Essex, after travelling from the Caribbean. The image of Caribbean immigrants walking down the gangplank has become an important landmark for British immigration. Britain was still recovering from the ravages of World War II and the restructure was underway. Buildings needed rebuilding and jobs needed filling. The young men and women on the Windrush, many of whom had served in the British armed forces, had answered the call to come to Britain. Many were keen to see the country that still ruled their homeland.

When they arrived they found an unfriendly welcome. They encountered racism and discrimination, and also doors closed to jobs, homes and friendship. Despite this many of the so-called Windrush Generation stayed and made a life here. In 1971 they were told that they could stay permanently but no record was kept of their status and some did not apply for a UK passport. Then in 2012 a change in immigration law meant that anyone without documentation was unable to access social services and some faced deportation. Others who had left were denied visas to return to see family and friends in Britain.

On 20 April, 2018, hundreds gathered in Brixton at Windrush Square, which was renamed as such in 1998 to recognise the importance of African Caribbean immigrants to the area. Speakers at the event, including Labour MP Diane Abbott, called for amnesty for the Windrush migrants. Journalist Gary Young said at the event: “I don’t want to live in a country that is hostile to migrants”. He said that the rally celebrated the massive contribution” of the Windrush generation, adding: “Black people helped build this country.”

A day later, on 21 August 2018, the then Home Secretary, Sajid Javid, announced that 18 members of the generation would get a formal apology from the government and anyone who had already left could return. Labour MP David Lammy, whose parents were on the Windrush, told the BBC at the time that the 18 were a “drop in the ocean”. He added: “The apology is crocodile tears and an insult to people still not given hardship fund, left jobless, homeless and unable to afford food.” The home secretary later confirmed that at least 11 people who had been wrongly deported had since died. Speaking in November 2018, shadow home secretary Abbott described this as a “complete disgrace” and pointed the finger of blame at the hostile environment policies championed by Theresa May while she was home secretary.

The appalling case of the Windrush Generation echoes the so-called Dreamers in America. These children of illegal immigrants still live under the threat of deportation and had at that time recently been used a political bargaining chip in a bitter immigration battle between President Trump and his Democrat adversaries. Too often issues of immigration are used and abused by the political elite. And every time real people are stuck in the middle in a state of hellish limbo.

A chill wind sweeps through Windrush Square. I walk past two young men with a stand giving out copies of the Koran. Their sound system keeps cutting out but they seem undeterred in spreading their message. Further up a group of young men gather around a bench and fiercely debate the core scriptures of Islam. Over the road is the impressive sweeping frontage of Lambeth Town Hall, juxtaposed against Electric Brixton next door, a venue with clean lines and dressed in the chic suit of grey and black.

On the square, the Ritzy Picture House cinema dates back to 1911 and had been carefully restored to its former glory. The Black Cultural archive further up is a sand coloured, modern looking building. It’s dedicated to preserving the record of Black British history and culture. Established in 1981, the centre aims to promote the public’s understanding of the contribution of African and Caribbean people to Britain.

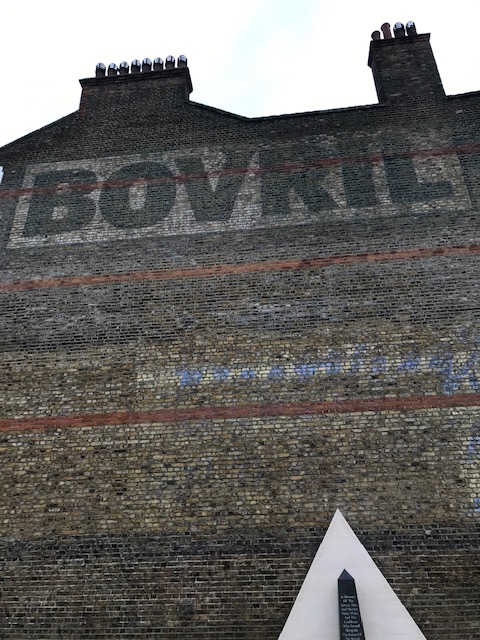

I approach a war memorial on the square, honouring the service men and women from Africa and the Caribbean who served in World War I and II. People heeded the call of King and country and came to fight from British Guiana, Grenada, Jamaica, the Leeward Islands and other nations. Poppy wreaths ring the memorial, including a jet black wreath right in the middle. I glance up at the building behind the memorial and see the word ‘BOVRIL’ faintly visible on an old advert painted on the brick.

Heading back to the Tube station, I take a pit stop in Brixton Market on Electric Avenue. Originally built in the 1880s, this was the first street market to be illuminated at night by electricity. It was also made famous in the 1983 Eddy Grant song, ‘Electric Avenue’. The place hums with smells, sounds and activity. Stalls sell a range of exotic produce from Africa, the Caribbean, South America and Asia. Barber shops and hair salons buzz with activity and debate. An ‘I Love Brixton’ sticker is proudly displayed in a Halal butchers.

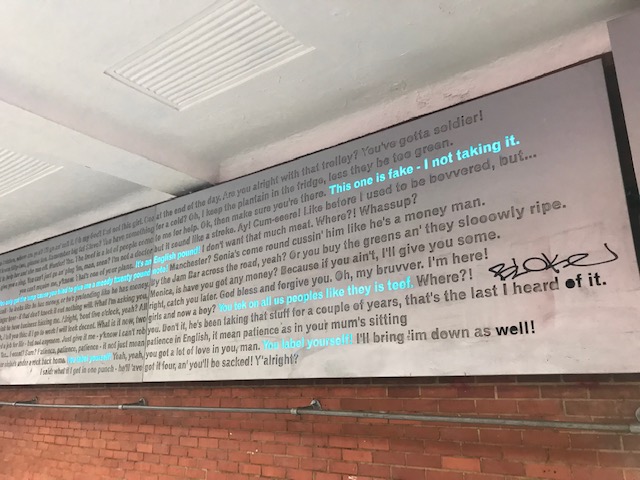

At the end of Electric Avenue, next to an Iceland supermarket, there’s an art installation for the Brixton Speaks initiative. A long metal plate has a variety of phrases cut from it and roving blue lights behind illuminate the fragments of speech that were recorded on the market in 2009. “This one is fake – I not taking it,” one message says, another warns; ‘You tek on all us people like they is teef,’ and another barks; ‘you label yourself!’ A message about the artwork from Will Self explains: “The aim of Brixton Speaks is not to antagonise, shock or distort, but simply to mirror the great vigour, invention and diversity of Brixtonians.”

Next to the artwork is a brass plaque commemorating that this is the site of the Brixton bombing. On 17 April 1999 – a busy Saturday much like the day I find myself in Brixton – a homemade bomb formed of fireworks taped inside a sports bag was left at Brixton Market. A market trader became suspicious of the bag and the man hanging around it. He moved the bag to the less crowded area further down Electric Avenue.

The bomb was moved two more times and eventually ended up around the side of the Iceland supermarket. The police were called and they arrived at 5.25pm, just as the bomb went off. Forty-eight people were injured, many from the four-inch nails that were blasted forth from the bag. Market trader George Jones, who had called the police after realising it was a bomb, was blown across the road and had a couple of nails lodged in his leg. A one-year-old boy was taken to hospital with a nail lodged in his brain.

The following weekend a second nail bomb went off on Saturday 24 April in Brick Lane, East London. Again the bag with the bomb raised suspicion and a man put it in his Ford Sierra car to take to the police station. It was parked on 42 Brick Lane when the bomb went off, injuring 13 people and causing damage to surrounding buildings. The weekend after the bomber struck again, this time at the Admiral Duncan pub. On Friday 30 April – the start of a busy bank holiday weekend – a sports bag exploded at 6.37pm. This time three people were killed and 79 were injured, many seriously. Four survivors had to have limbs amputated.

The London nail bomber was eventually revealed to be 22-year-old David Copeland, who was a Neo-Nazi militant who had formerly been a member of far-right groups, the BNP and National Socialist Movement. With each bombing he had deliberately targeted minorities – Brixton has a large African Caribbean community, Brick Lane was home to many British Bengalis and the Admiral Duncan on Old Compton Street in Soho was in the heart of London’s gay community. Copeland was convicted of murder in 2000 and handed six concurrent life sentences.

Following his arrest, Copeland had a written exchange with BBC reporter, Graeme McLagan. He appeared unrepentant for his crimes, writing; “I bomb the blacks, Pakis, degenerates. I would have bombed the Jews as well if I’d got a chance.”

Asked why he had targeted Ethnic minorities, he said: “Because I don’t like them, I want them out of this country, I believe in the master race.”

On the plaque memorialising Copeland’s hateful crime in Brixton almost 20 years ago, the inscription reads: “A community under attack will not be divided. Together we are stronger.”