The End of the Line is a 10-part travelogue journey to some of the highest Remain and Leave areas in the United Kingdom’s 2016 Referendum on EU membership. It was written over two years from 2018 to 2020, before Coronavirus made Brexit seem like a spot of man flu.

Bristol voted 61.7% Remain in the EU Referendum

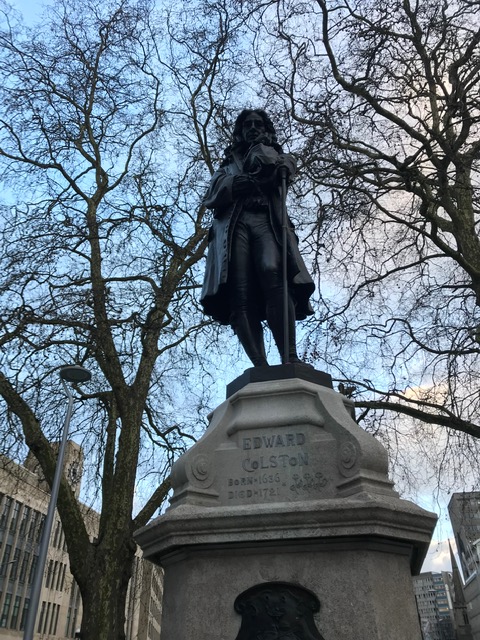

Originally written in March 2019 (before Edward Colston ended up in the drink)

Bristol’s always been a place that has evaded me. Not literally, of course, as cities don’t tend to move around that much. But rather nothing in my life ever took me there. The only time I ventured to Bristol was for a few hours spent at Bristol Temple Meads railway station with other festival goers waiting to head to Glastonbury by minibus. That was 1997, the year when Tony Blair stormed to power on a wave of big political dreams and a sound track of D-Ream. ‘Things, can only get better,’ the band belted out. Well, yes and no, as it turned out.

Pretty much the entire South West of England voted to get out of the European Union. The five anomalies in the more than 25 region block were South Hams, Exeter, Bath & North East Somerset, Mendip and, of course, Bristol. These remain redoubts now sit like blue lily pads, bobbing on angry ripples of a vast yellow sea. If so many of their neighbours wished to leave the European Union, why did Bristolians prefer to remain?

I take the train from Brighton to Bristol, changing at Fareham near Southampton. On the first leg of the journey, two men board my train carriage clearly in the thralls of a thunderous hungover. A whiff of stale beer and cigarettes wafts from them as we cross the river Adur out of Shoreham and past the airport. The man with the bigger beard and a nose ring leans his head on the window glass and says to the other, ‘Wake me up when we get there.’ The other man replies, ‘That means I am going to have to be the responsible adult.’ But his travelling companion is already asleep.

To keep himself awake, the man cracks open a pint can of Monster energy drink and takes a sizeable slug. A free table becomes available and they move over, with one remarking kindly; “Let’s move before we stink up the place.”

After they have settled, he orders his friend. “Now back to sleep with you.” The other happily obliges.

The sky outside is grey and pregnant with rain. The air already appeares damp but it’s clear that a greater deluge is on the way: the kind of rain that never relents and never seems likely to stop, until of course, it does. A misty haze hangs over the stippled green fields as we roll through the Worthing stations. East Worthing, Worthing and West Worthing: why a relatively small West Sussex town needs three station remains a mystery. Worthing voted Leave by 53%, as did neighbouring Adur (54.6%), Arun (62.5%) and Chichester (50.9%). By contrast Horsham, Mid Sussex, Brighton & Hove and Lewes all voted Remain, with the biggest margin being Brighton.

The flat landscape outside extends onwards, seemingly without limit. The sea of dull brown is punctuated periodically by the odd town or settlement. The garishly bright yellow puffer jacket worn by a boy sitting across from me begins to give me a headache. He has man-spreaded so successfully that, even though we are on a table of four with two empty seats, I feel thoroughly boxed in. Outside, gnarled and naked trees stand starkly, waiting for more bountiful seasons to return. The hungover man gets off at Chichester, pulls his hood up and stumbles towards the exit and presumably a welcome bed somewhere.

Chichester station has a Waitrose next to it. You can always tell a posh place if there is a Waitrose. According to a 2018 report by Lloyds Bank, a home near a Waitrose supermarket sold for 12% more than the average for that neighbourhood. You’d get a value bump, too, if you live near a Marks & Spencer or branch of Sainsburys, but Waitrose remained the golden ticket for middle class England.

Just outside of Nutbourne, a tatty Union Jack floats in the wind on someone’s conservatory. Onwards we go through fields punctuated by clusters of identikit new build homes forming new towns with humorous names, like Warblington. The man-spreader gets off at Havant, and I enjoy a momentarily delicious return of my freedom of movement, only for a woman to replace him and block the entire table with her huge suitcase.

At Cosham, a woman waves at the train with a look of sheer terror on her face. She looks right at me, but also beyond me. Should I wave back? Will she curse me if I don’t? Is she a ghost of a passenger lost in the never ending delays that blight our railways? She is at once a warning from the past and the future. By the time I have decided it’s probably best to hedge my bets and wave back, we’ve already long left the station. Outside, rows upon rows of houses roll past the train. Each has its own story to tell. Laughter, tears, love, hate. Christmas arguments, birthday surprises, shouting matches: all the stories I will most likely never get to hear.

Finally we arrive into Fareham and a short wait to get the connection to Cardiff that stops at Bristol Temple Meads. A bitter wind lashes the open station, cutting me to the bone. I step from one foot to the other to keep warm until the three-car train arrives. I take a seat at a table. A woman opposite me gives me a disapproving look for disrupting her afternoon with my desire to sit down. She peers at a magazine with mouth open a sliver, as if slowly sucking up the printed words and pictures.

“Can I get a coffee at Eastleigh?” she asks the passing conductor.

“Yes,” comes the reply. “There used to be a trolley service on this train but that went in the cuts.”

“Oh,” the woman says, full of concern. “What a shame.”

She dutifully gets off at Eastleigh, bearing what appears to be the entire contents of clothing shop Primark in a series of large paper bags, forcing me to duck out of the way as she passes.

At the station a huge group of middle aged women get on and embark on a chaotic journey to find seats together. ‘One there, one there, one there,’ a woman with frizzy hair bellows at the others behind her. They fret about two people who have sat further down the carriage, until they are shamed into re-joining the group. Bags of crisps, sausage rolls, sweets and other snacks emerge in a festival of chomping. ‘Anyone want a chocolate mini-egg?’ ‘Sausage roll?’ ‘These are gluten free?’

My stomach rumbles.

The rain that was advertised earlier has now met its delivery slot. A thick soupy haze hangs in the air. The train approaches Westbury. The group of women conduct a similar kerfuffle when getting off the train, with the frizzy haired lady once more acting as the cox.

“It’s this stop, get up!” she bellows.

“Alright Elaine, you’re not the conductor!” another woman responds.

They all get off. One woman, called June, straggles behind and they urge her to hurry up. She looks at me smiling as she goes past.

“Now you can have some peace!”

I smile back.

In the far distance out of Westbury you can see the White Horse, a giant horse embossed in the hills and the oldest such marking in Wiltshire. The skies darken further as we near the beautiful sandstone buildings of Bath Spa. Sizeable estates stand guard over the lush green countryside. Towering manor houses watching over everything they survey. Rugby pitches dominate over football. Then can be seen long, proud rows of attractive houses. Everywhere, wealth pervades.

Eventually, the train arrives into Bristol Temple Meads station and I get off. Although the station is grand in scale and appearance, the area around it at the time is definitely a work in progress. A messy tangle of road works herald development, but right now create a circuitous and laborious maze to navigate into town for the pedestrian. Every passage appeares to be blocked either by plastic barriers or exhaust fumes. Eventually I emerge, slightly bewildered, close to the harbour and spot for the first time the lovely, brightly coloured rows of houses that gild the cliffs around Bristol harbour.

With an estimated population of 459,300 people at the time, Bristol is the largest city in the South West of England. It’s a youthful city, with more children under sixteen than people of pensionable age. Like Brighton and Liverpool (similar shipping history and also voted Remain at 58.2%), but also Amsterdam in many ways, Bristol is a place where wealth, history and youth combine to create somewhere unique. It’s a place of substantial development. Bristol City Council has committed to building more than 2,800 new homes in the city in the 2019/20 financial year. The area around Bristol Temple Meads was designated as the first of the Enterprise Zones in the 2011 Budget. Some 11,000 homes were to be created in the 70 hectare site and the station given an upgrade. As I walk over the canal a barge boat hangs a big banner for an Abolition and Slave Trade Memorial. The message states; reconciliation, remembrance, reflection. As I will find over the course of my visit, Bristol is a city eagerly eyeing the future, but also grappling with its past.

Leaving the spaghetti junction of road works, I reach Queen Square. A group of tourists are receiving a tour and I stop to steal a few eavesdropped moments of local history while pretending to inspect the statue of William III on his horse. I head further into town. Bristol’s a cool place. Trendily dressed young people mooch about town, some ride on bikes in convoys like you see in Amsterdam. There are huge graffiti murals, celebrated as pieces of art rather than just urban blight. Shoppers browse eye-catching vinyl albums in Rough Trade Records.

The precinct ahead is more akin to any English city. All the usual chains are here and teenagers hang about trying to entertain themselves. A lad on his bike deliberately blocks my path and chuckles as I have to walk around. I ‘tsk’ and shake my head at him as is the way to register displeasure without getting a right good kicking in return. There is an edginess to Bristol town centre, but no more than anywhere. The wind dashes through the precinct, the earliest warning of the coming Storm Freya. It had already been dubbed a ‘killer storm’ by the papers but no one seemed overly bothered here.

“Still better than last March,” the barman in the Drawbridge pub says as he pours my pint. “Made a right mess of my garden.”

Everton are playing Liverpool and it is being beamed out on giant tellies throughout the pub. Outside, a couple of street drinkers walk down the road, bellowing at each other. The barman clearly knows them well.

“Who’s that bloke e’s with?” a drinker asks at the bar at the kerfuffle outside.

“That’s his wife!” the barman replies.

The row outside starts to settle down, as other homeless people gather with the group. Sleeping bags are draped round their necks as they try to fend off the already freezing temperatures.

“Hope they’ve got somewhere to go tonight,” the barman says as he cleans some glasses.

After finishing my drink, I take a walk down the waterfront area. Alongside the Watershed pontoon, people slumped in shop doorways periodically emerge from the gloom to ask for change or a cigarette. According to figures from Bristol City Council, there were 82 rough sleepers in Bristol in late 2018, the fifth highest number nationally at the time and up by around 50% on 2014’s figure. Thanks to a tough economic climate and skyrocketing rents in the city, many have been left without a home. The city council’s rough sleeping team had contact with 951 people in 2018, up 23% on the previous year. The gaggle of street drinkers seen outside the pub earlier passes me as I head back towards King Street.

Small Bar turned out to be, in actual fact, not that small. Behind a thick wooden bar stand two trendily dressed people serving up advice on all the beer selections on offer, and periodically taking orders for fried chicken and burgers served in plastic baskets. A small tuck shop offers a range of retro snacks, such as Kinder Eggs and Pickled Onion Monster Munch crisps. Art on the walls appears to have come from am upmarket tattoo parlour. The tables are formed of old scaffolding tubes and joints, and there are the inevitable filament lightbulbs hanging from the ceiling.

Still, though, it’s a nice enough joint with a bubbly, youthful clientele. A woman with strawberry blonde hair talks loudly and with ferocious speed about everything from her art to her daily Pilates routine. The bearded man she’s with nods, smiles and laughes heartily at all the right places. Time to move on. The King William is opposite Small Bar, in more ways than one. It’s a Sam Smith’s pub and so has both cheaper prices and more grizzled drinkers. A group in the front bar decides not to even bother hiding that they’re topping their pints up with cans brought with them. The barman appeares to have stopped caring a long time ago. I order a pint of Taddy Lager (imagine a beer made from diluted cordial) and head to the back of the pub. A couple are deep in conversation but look up at me as I take a seat.

“Is she bothering you?” the man asks me, motioning to the woman, “because she sure is bothering me!”

They laugh at the tediously predictable joke. I manage to muster a weak smile in return and hope that this is the end of the audience participation.

It’s getting late and my stomach is wondering why I am ignoring its clear and unequivocal rumbles. Before I seek sustenance, though, I am tempted sufficiently to pop into Kongs of King Street, a trendy loft style bar with neon, craft beers and retro video games. A row of arcade machines sits at the back of the bar. I buy a pint and then play Megaman, quickly realising that I have no idea what I am doing and have always found this game deeply annoying. Instead, I sit down and watch a group of friends play the Tekken fighting game on a projector screen. A panda is selected to fight an obese man on an exploding oil rig. I share a bemused look at the combination with the two underage drinkers also watching the action close to me. When in Rome, I guess.

Dinner is had at Pieminister, an expanding Bristol-based chain serving up, well, pies. The service is somewhat chaotic that evening, with staff appearing stretched despite it being 10pm and the restaurant relatively quiet. The pie is well received when it arrives, though, with thick, rich pastry and a good filling, plus decent gravy on the side. I pay up and head out into the cold, night air. A couple of street drinkers argue over something outside my hotel, barking in incoherent angry slurps. ‘Hope they have a bed for the night,’ I think. I feel guilty that I have a warm and cosy hotel room to myself, but soon sleep takes me.

Clifton Down

I wake up, unsurprisingly, in the same hotel room on my own. Today is my 40th birthday. Forty years spent living in England. Forty years on planet Earth, and all I have to show for it is the foresight to buy a breakfast sandwich the night before from Sainsbury’s. I make a cup of black coffee (never trust UHT milk) and tuck into my meagre birthday breakfast bounty. Maybe I will wrap up the shower gel and then I can pretend that someone bought me a present to open. No, mister, you just sit there and eat your sandwich and think about what you’ve done.

After showering the tears out of my eyes (joke), I check out of the hotel and head off to explore more of Bristol. As you might have noticed, Bristol Temple Meads isn’t at the end of the train line. There were a number of reasons why I was drawn to this city, but I have started the End of the Line shtick now, so had better convolute some reason to be here. Clifton Down station is therefore my destination today. If you don’t like it, write to your MP and they can ignore it, too. I walk down by the quay side, past the Andolfini Contemporary Art Gallery and over the bridge to Wapping Wharf. A café has cable spools overturned and made into tables. Thick metal links sit in bunches on the floor for the boats to tie up to. Red-faced joggers pant their way across the cantilevered bridge. Cool-looking kids wearing big headphones head to work or University or to play ironic Tekken.

Heading onto the wharf you can see the giant shipping cranes, stretching up like industry edifices. In the 1300s Bristol was the second most important city after London. This had been made possible after the River Frome had been diverted to create a wider channel able to take bigger ships into Broad Quay, just further up from Wapping Wharf. In the 1400s the trade with France declined and merchants looked farther afield for riches, to the Far East and also eventually, Africa and the Caribbean.

Bristol remains a working port city, but it has moved with the times. Around the corner from the cranes, shipping containers have been stacked and converted into a venue for shops and cafes. Further up past the dockside railway, a modern complex of flats promises quay-side views. It had started to drizzle when I reached the SS Great Britain, the first propeller-driven, ocean-going, iron ship to cross the Atlantic to America and the largest passenger ship of her day in the late 1840s. The ship was designed by a genuine British genius of industrial design, who could arguably claim the title for best name in history, Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

The SS Great Britain, along with the earlier SS Great Western, had revolutionised ship design. Brunel died shortly after the ill-feted launch of his industrial, sea bound monster. It had a controversial life, but still made its mark. Brunel seemingly could turn his mind to any design challenge. It was his original design that was adapted by William Henry Barlow and John Hawkshaw to create the Clifton Suspension bridge that spans Avon Gorge over the River Avon, linking Clifton with Leigh Woods in North Somerset. The Grade 1 listed bridge remains a symbol of Bristol to this day.

The clouds above me darken as I move on through the dockside, passing the Underhill working shipyards filled with various businesses, from ship buildings to artistic iron workers. The South West accent has a wonderful sing-song lilt to it.

“You wan me tow bring ‘em dowen, or rrr yoo gon come ‘erp?” a man in overalls calls from the top of a ship being repaired to an unseen colleague. I can’t help but smile at the sound.

I head on over Spike Island (not to be confused with the island in the Mersey where the Stone Roses played a notorious 1990 concert) and then travel up to Clifton. Halfway up the ridiculously steep hill, and with nowhere to shelter, the clouds open and the rain pours down in an absolute deluge. Happy birthday to me, happy birthday to me….

I can just about make out a pretty row of dockside cottages as slicing cold sheets of rain batter my face in diagonal lines. It’s the type of relentless rain you get occasionally in England. Most time it’s just a drizzly cold war of attrition, but on occasions that escalates into extreme atmospheric bombardment. I scan the submerging scene desperately for a coffee shop but my glasses have steamed up to such a degree that I am temporarily debilitated. I stagger about like Mr Magoo, my clothes getting more saturated and tighter with every step. In a mad panic I plough up Granby Hill and immediately regret relying on Google Maps. The road proves to be a near vertical grind up the hill, all the time the weather slapping me around the face like a dandy goading me to a one sided duel.

Eventually I reach the top of the hill and the salvation of a coffee shop. I stumble inside, sit down and watch through the window as the rain magically stops and a sliver of sunshine punctures the clouds.

‘Well played, weather,’ I think to myself. ‘Well played.’

My clothes are so soggy and wet that they had begun to steam. My hair (well, what’s left of it) is slapped to my forehead as though I am Lego mini figure that didn’t pass quality control. I shiver and clutch my coffee for warmth. Meanwhile, at a nearby counter a woman is eulogising about the benefits of eating dates.

“Before I came here I just thought they were for my grandma,” she says happily to the waitress, who is politely showing interest.

On another table a bald man talks loudly on his phone while staring at a spreadsheet on his Macbook with an expression of mild irritation. Another lady enters, orders a lemongrass and ginger tea, and finds a seat.

Outside I see the Clifton Village Fish Bar, with a sign in its window proudly stating that it is in the top 100 fish and chip restaurants. But where, I wonder? Is it 1st place or 99th? That seems an important bit of information to know. Much like Bath, Clifton Village exudes wealth. The average price of a house sold in Clifton over the past year was £436,076, almost twice the national average property value of £225,621. The average price of a flat sold in Clifton was £349,838, a terraced property would set you back £699,533, while you’d need more than £1m for a semi-detached house, according to data from Right Move.

You can understand why people would want to live here. Tall sandstone buildings stand elegantly around well-presented squares. Boutique shops and cafes line the main roads. Expensive cars sit parked up waiting for their owners. The Clifton Suspension Bridge is not far away, and nearby it the Clifton Observatory. The view from there is staggering, with the sweeping bridge straddling the gorge and the undulating Somerset hills further ahead. If I wasn’t damp and freezing cold, I would have stayed and enjoyed it for longer.

Dropping down through the park at the back of the observatory I soon find myself on Clifton Down, a grand road that curves around the Cliffside green space. The road is lined on one side by huge buildings that were clearly once the homes of very wealthy individuals (and, no doubt, many still are). Here the fortunes made from shipping and maritime industries forged mansions for the prosperous and fortunate. Eventually I find Clifton Down train station. This used to be a through station but now trains go just one way from both platforms towards Avonmouth, Bristol Temple Meads and, an actual end of the line station, Severn Beach in South Gloucestershire. Severn Beach is just 24 minutes away from Clifton Down station, yet is located in a region that voted 52.7% to leave the European Union. The reasons for such a scenario are presumably too complex to generalise, but it is perhaps telling that the average house price in Severn Beach is £235,184, nearly £200,000 less than the average for Clifton. At that rate you are losing just over £8,000 in property wealth for every minute of the train journey.

Clifton Down station is pretty nondescript. It has two platforms, but with just one way in and one way out (with a disused tunnel in the other direction). The platforms are dingy and dank, being in the shadow of the brick mountain that is the back of the Clifton Down Shopping Centre. The drizzle continues as I walk down the platform. A woman asks me where she can get a ticket for the train. “Ah,” she says after I point her to the ticket machine she is standing right next to. I walk up the stairs to leave. A homeless man stands at the top taking shelter from the rain.

“Good morning,” he says, before correcting himself. “Good afternoon, I should say. It’s nearly 12.” He peaks around the corner and points at the clock on the tower of Tynedale Baptist Church. “That’s how I know what time it is. That’s how I know.”

I exit the station and head towards Whiteladies road, passing the Black Boy Inn. Both names have had rumoured connections to the slave trade, but both with no clear basis in fact. Same is true for the myth that slaves were brought from Africa and held in caves under Redcliffe before being auctioned off. There is no evidence to support this, but an unchallenged myth has a habit of morphing through repetition into historical ‘fact’. However, Bristol does have a long association with the slave trade, and the modern city continues to grapple with its own complicated history. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in the connection with one of Bristol’s most famous sons.

Edward Colston was a wealthy shipping magnate in the late 1600s, who became famous for his philanthropic work in the city. A significant chunk of his fortune came from the slave trade. During his time at the Royal African Company, it is estimated that between 1672 and 1689, Colston’s ships ferried around 84,000 men, women and children from Africa and the West Indies. It is believed that around a quarter – more than 20,000 people – died during the journeys as conditions were so bad.

There’s a statue of Edward Colston in the town centre of Bristol. When I visit it, the man looks down on me with disdain as I stand at his feet. The accompanying plaque says; ‘Erected by the citizens of Bristol as a memorial of one of most virtuous and wise sons of their city. 1895’. However, for much of Bristol’s population, the statue and the legacy of Colston jar with the modern world they live in. Bristol is a diverse city, with 16% of the population belonging to a black or minority ethnic group. However, a Runnymede Trust Report released in 2018 showed Bristol has the greatest disparity between white and ethnic minority communities anywhere outside of London.

Understandably, having a statue to a known slave trader has attracted protests. Graffiti drops of blood were once placed on it (rumoured to be done by Bristol artist Banksy). A red ball and chain was placed on Colston’s leg in May 2018. Rather less subtly in the 1990s, someone daubed ‘fu*k off, slaver trader’ on the statue. When I visit in March 2019 a guerrilla art exhibit had been placed at the statue involving human figures laid at his feet and words written on boards saying things like ‘sex worker’, ‘fruit picker’ and ‘kitchen worker’ in reference to the modern slavery that now blights society. Trafficked people from Lithuania had only been recently found locked up in a home on Hathway Walk in east Bristol.

There had been calls to take the statue down, in a similar way that statues of Confederate figures had been removed from parts of the United States. But how do you unpick Colston from the city? His name is everywhere: from streets to buildings, to pubs and halls. Every mention is a reminder that the city was made, in part, on the backs of slaves. Edward Colston’s statue sits on Colston Avenue opposite music venue Colston hall. You might as well call Bristol, ‘Bristol – brought to you in association with Edward Colston.’

However, the city is now quietly trying to shake off this controversial patriarch. The St Mary Redcliffe and Temple School said in February, 2019, that it would rename a house bearing Colston’s name to ‘reflect diversity’. It will instead become Johnson House, in honour of NASA mathematician Katherine Johnson. Assistant head Karuna Duzniak told Bristol Live: “We cannot change the past, but we can change the future.”

Such moves have inevitably stirred feelings of resentment among certain communities that they were being made to feel guilty or ashamed of Bristol’s history. Although there are clear tensions, it feels a healthy sign for a city to confront and challenge its past. Just as is happening with the Windrush Generation in Brixton, sections of Bristol’s society are beginning to ask important questions about the city’s past. Dealing with such a past does not mean that you were guilty of the crimes, or should carry the shame. Rather, to honour history means to confront it and to be prepared for answers that run counter to the prevailing view.

The Black Boy Inn is closed when I walk past so instead I go to the Jersey Lily for a pint. A big group arrives for lunchtime drinks, possibly from a local business. Another group near me discusses such diverse topics as computer hacking and being in the army. I finish my pint and then head back to Bristol Temple Meads to go home. Down Whiteladies Road, I pause as a man carries a 55-inch 4K television from Richer Sounds to his BMW. Across the road are two sofa shops – Sofa Shop (no prizes for that name) and the intriguing Sofa Library. You could imagine a terse silence inside as people pour over tomes detailing the history and theory of sofa design, punctuated by the occasional polite cough.

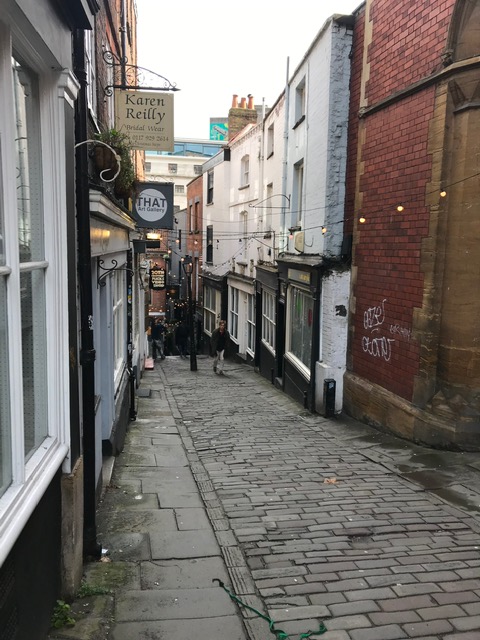

Veering off the main road I head onto Cotham Hill and down through the University district. Students are out for lunch and there’s a big queue for Parsons bakery. I take a meandering route back towards the station. More university buildings pass, some stylish and new, others old and austere. Then the Christmas Steps, one of the oldest streets in Bristol, this stepped way’s name is thought to derive from a bastardisation of its previous title, Knyfesmyth Street. Or it could come from nativity scene on the window of The Chapel of the Three Kings of Cologne at the top of the street. Or it could be just because Christmas Steps sounds good and attracts the tourists.

The River Frome originally used to run at the bottom of this steep hill and barrels would be rolled down the steps to waiting ships at the bottom. As with most things in Bristol, the sense of history is balanced always by the modern. Classic vintage shops are juxtaposed with trendy art galleries and a pub that’s dark inside for a deliberate reason. A man asks me for directions as I stand looking up at The Christmas Steps pub pondering another drink. I shrug and explain that I am not a local.

“Ah,” he says. “I used to come here when I was kid. It’s changed so much, I don’t know where anything is anymore.”

Crossing over the pretty Queen Square, I walk past the statue of William III once more. The edifice, which depicts William looking majestic on horseback, was erected in 1736 to mark Bristol’s support for the Crown and Parliament Recognition Act 1689. This rather bizarre piece of legislation, which stands to this day, declared that James II had abdicated, when in fact he had been allowed to flee to France after William had invaded England with the backing of the political elite and a rather sizeable naval fleet.

With James gone, parliament could not hand the crown to William of Orange until it had some sort of legal standing to do so. Hence the Crown and Parliament Recognition Act 1689 came into force, effectively saying, “Some really illegal stuff just happened but it’s OK because this gives it the rubber stamp of approval, so we’re all good, right?.” They would have loved Brexit, I think to myself. I look up at William’s statue. His face gazes fiercely towards the horizon, as though surveying another country to invade. A pigeon then defecates on his head, with the residue rolling down his cheek in a solitary white tear.