The End of the Line is a 10-part travelogue journey to some of the highest Remain and Leave areas in the United Kingdom’s 2016 Referendum on EU membership. It was written over two years from 2018 to 2020, before Coronavirus made Brexit seem like a spot of man flu.

Tendring voted 69.5% Leave in the EU Referendum

Originally written in March 2019

Clacton-on-Sea has a history of fending off European invaders. Along the glorious sandy beaches of the Tendring coast lie dotted Martello towers – remnants of the coastal defences against the threat of a seaborne invasion by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. Some 29 such towers were constructed in a fortified line running from Brightlingsea to Aldeburgh between 1809 and 1812. Each cylindrical tower was formed of 750,000 bricks, making the walls two to three meters thick and capable of absorbing a direct canon shot. They were armed with three canons, and a gun battery usually sat nearby. Each tower was designated with a letter, with towers C, D, E and F standing dutifully in watch from Jaywick to Clacton.

In the end the invasion never came as victory for England in the Battle of Trafalgar secured British control over the seas. Besides, Napoleon had become distracted by the new threats from Prussia and, in a common bête noir for your power-mad European dictator, ill-advisedly taking on the big bear of Russia to the East. Now, the Martello towers stand as stout monuments dominating the coast, permanently marking the threat that can be posed by an unshackled European power, real or imagined.

Although Boston in Lincolnshire recorded the highest proportion to vote Leave in the 2016 EU Referendum, in many ways it is the east coast of England that can lay the claim to be called ‘Brexit country’. Of the top five highest Vote Leave areas, three were in the East of England – Castle Point 72.7%, Thurrock 72.3% and Great Yarmouth 71.5% (the others were in Lincolnshire, including Skegness). Of the entire region only Norwich voted to remain in the UK. Tendring, including Clacton-on-Sea, voted Leave at 69.5%, well above the national average for England at 53.4%.

On a pallid grey Friday on 1 March 2019, I set out to visit Clacton. This day marked the near month-long countdown to Britain supposedly crashing out the European Union on 31 March, 2019. My Dad accompanies me on the trip. He used to live in Essex and we’d come to Clacton-on-Sea in my late teens for day trips. My Dad had separated with my Mum when I was 15 in 1994 and then later moved to Essex to work at the University. I’d come down for occasionally awkward yet generally fun weekends when he lived in the village of Wivenhoe, and then spend equally fun yet also equally awkward days out in Clacton, enjoying the attractions on the pier, walking the promenade and eating heaped plates of fish and chips.

On this spring day, the train we intended to get from London Liverpool Street was cancelled, a situation so common when travelling by train in Britain that one barely raises an eyelid anymore. Indeed, on every single trip I have made on The End of the Line, at least one train has been cancelled, delayed or disrupted in some fashion. We instead board the train to Colchester and change for the Clacton connection. Heading out of London the sky hangs as a dull grey shroud, a state exacerbated by the thick grime on the windows of the carriage. You can just about make out the Olympic Park at Stratford to the right, home of the London 2012 Olympics. The double helix of the red Arcelor Mittal tower pokes out from the ground and the London Stadium sits like a black and white basket dropped in the centre of the park. It’s now home to football club West Ham United.

A woman across from us frets about her ticket. The inspector had appeared and she couldn’t get the electronic ticket to display on her tablet.

“I’m not one of those people,” she urges to those seated behind her, somewhat desperately. “I have bought a ticket. I’m an honest person!”

She eventually manages to get the device working and lifts up the two seat trays laden down with make-up and hair straighteners to go in search of the inspector, who seems decidedly uninterested as to whether she had a valid ticket or not. She returns, mightily relieved, and promptly phones a friend to replay the entire tale.

A man bedecked entirely in a hue of beige restricted mainly for hearing aids waddles down the aisle and then, for some unknown reason, immediately waddles back again. Outside London chugs and chugs before eventually running out of steam. The sprawling outer suburbs amble into view as we move further and further towards the county of Essex. Upon arriving in Colchester, we face a twenty minute wait until the 11.16am to Clacton is due to arrive. So, we buy a dreary-tasting cup of hot brown liquid from the station café and my Dad somewhat wearily regails me of his commuting stories.

He had moved to Surrey part way through working for the university and had to do the long commute across the whole of London to get to work. It clearly isn’t a happy of memory for him, so I try to move the conversation on, but with the usual carnival of rail cancellations and delays in full force today, it isn’t so easy to break out of the painful reminiscences. As a commuter myself, I can sympathise. It’s like we are in a mundane version of Vietnam. If you enjoy the privilege of being able to walk to work, all I can see is; ‘you weren’t there, man, you don’t know!’ Some excuse of a broken down train flutters around the station loud speakers. Seasoned rail users tend to drone out such platitudinous piffle. The 11.16am is announced on the loudspeaker as arriving but after there’s no sign of it at that allotted time, the announcer decides it is best that it is now the 11.18am instead. Seriously.

The train eventually rolls out of Colchester and we pass the functional architecture of the University of Essex complex. Dad worked here from 1995 to 1998 and lived in the area up to 1997, when he moved to Surrey and commuted back to Colchester. A grey haze hangs over the complex as we zip by – Dad looks out as a substantial chunk of his life appears and disappears in a matter of seconds. We soon arrive at the pretty village of Wivenhoe, where he used to live. The timber clad buildings and cute cottages give it a quaint feel. He’s now retired and busying himself on a genealogy project. From his research (which I am rather cruelly revealing before he has had time to publish) our family lived in the area in the 1700s and 1800s. Wivenhoe was home to many generations of the Willis Family – of which my grandmother, whose maiden name was Willis, was part – from 1772 until the 1880s. The majority of the Willis males during this time were Seamen, Master Mariners and Shipowners many of whom sailed out of the Port of Colchester.

The flat landscape outside seems to go on forever. We roll through fields of mobile homes just outside the fabulously named, Weeley Heath. Onwards to Thorpe Le Soken, with the station surrounded by carcasses of derelict buildings, clinging on life support via a scaffolding exoskeleton. You can just about make out a quite pretty village beyond the Soviet bleakness. Eventually we roll into Clacton-on-Sea – all change, end of the line.

Clacton-on-Sea is a seaside town on the Essex sunshine coast that was and still is one of the most Eurosceptic towns in the UK. At the time of the 2016 vote, Clacton had 16 Ukip councillors and Britain’s only Ukip MP, Douglas Carswell. It is represented at the time of our visit by Giles Watling of the Conservative party. Watling first contested the seat in 2014 but lost to Carswell. He eventually won the seat in 2017 after Carswell, who had subsequently left Ukip and gone independent, did not stand at the election.

Ever since Ukip’s system-shocking third place finish in the 2015 general election with 12% of the vote, the Eurosceptic movement had been on the rise. Despite numerous gaffes, controversies and ill-advised Facebook rants, the movement continues to gain support in communities like Clacton, which have a high percentage of the population being of pensionable age. It is predicted that within 20 years 60% of Clacton’s population will be 60 or over. Although not guaranteed, this scenario can lead a place to lean towards more reactionary approaches to developments.

In 2014, an attempt to turn a former beauty salon on Pier Avenue into Tendring Islamic Cultural Association was met with strong local opposition, fuelled by intervention by the English Defence League (EDL) but with solid local support. The cultural centre had been originally rejected by Tendring Council, yet that decision was overturned by a planning inspector on appeal based on the belief that it would be beneficial to the rejuvenation of the town centre. However, it was reported that locals felt their views had been ignored during this process, and they found the EDL more than willing to listen.

We head down Station Road towards town. Various businesses line the street – estate agents dominate, alongside financial advisors and a scattering of funeral homes (one of which appears to have recently departed this world). A group of boys, riding bikes and wearing track suits, do wheelies as appears to be en vogue again. One tries to play chicken with us but I decline to move and he blinks first.

They observe my Dad’s white hair and beard. “Hello Santa!” one boy says to my Dad as he passes, which, admittedly, does raise a smile.

We head towards the sea front, across the precinct at the bottom of Station Avenue and onto Pier Avenue, a tight single lane road down to Marine Parade on the front. The Magic City arcade hums away on the right hand side of us, with brightly coloured buzzing machines lined up outside and processional banners pronouncing that it has an ATM inside in case you’re short of cash. On the other side is Amusements Gaiety Amusements, a clunky but base-covering name if ever there was one.

“Molly, get back here!” a woman in a tracksuit looks up from smoking to shout at her dog, soaked through as it bounds up to greet us. “Not everyone wants a wet dog bothering them.” We smile politely and side step the animal, which is now more preoccupied with trying to chew its own backside. We’ve walked down the coastal walkway and are now on the thick sand of the beach. It brings back pleasant memories of being here all those years ago. Martello Tower E sweeps into view.

The towers were original clad in white render but that has long ago been lost to the harsh winds whipping off the sea. According to the information board in front, it was somewhat bizarrely converted into a family home after the Napoleonic War finished and then in 1938 it became a water tower for the new Butlin’s Holiday camp. Clacton was the second site chosen by Billy Butlin for his burgeoning holiday camp empire, the first being Skegness. Butlin’s second camp was built on the West Clacton estate in 1936. It opened in 1937 and added a camp site a year later, able to accommodate 1,500 holidaymakers.

Just like Butlin’s in Skegness, the army took over Clacton Butlins in 1939. A plan to turn it into a POW camp complete with barbed wire and flood lights enraged the locals and was eventually dropped. Instead the camp was used to house the survivors of the Dunkirk evacuation. While Skegness Butlin’s was left in a reasonable state after the war was over, the Clacton site was a mess and it wouldn’t reopen to holiday makers until spring 1946. During the 1950s and ‘60s Butlins Clacton grew rapidly, adding chalet accommodation and increasing capacity to 6,000. Cliff Richard made his professional debut at the camp and it was featured in the closing credits of popular BBC sitcom ‘Hi-de-Hi’. Just as with Skegness, Clacton Butlin’s hit problems in the 1970s with the rise of cheap holidays to Spain and other sunny European destinations. In 1983 the camp closed down – at the time it employed 900 seasonal staff.

A buyer was found for the site and it reopened as the Disneyland-style Atlas Park in May 1984, but that lasted just four months before the owner hit financial problems. Everything left in the park was auctioned off and the land sold to developers, who turned it in the housing estate that sits on the site to this day. The estate utilises some of the original chalets and footprints. It feels a long time, though, since you could hear the call of the Butlin’s red coats echoing around the coast. Tourism remains a key part of the economy in Tendring, estimated to be worth more than £1m a day in revenue and accounting for 16% of jobs in the district.

We walk further onwards towards the next Martello tower. It is somewhat dilapidated and in need of repair compared to Tower E. Next to the beach is Clacton-on-Sea Golf Club. A group of men stand around waiting to tee off as we walk past. They’re all dressed in expensive looking golf gear and guffaw at a shared joke. One of the men approaches the tee, steadies himself, sucks in his sizeable gut and then hoofs the ball around 10 yards straight into the water trap. He tries to style it out, as though he meant to do such a thing purely for amusement, but his friends had already begun the mockery.

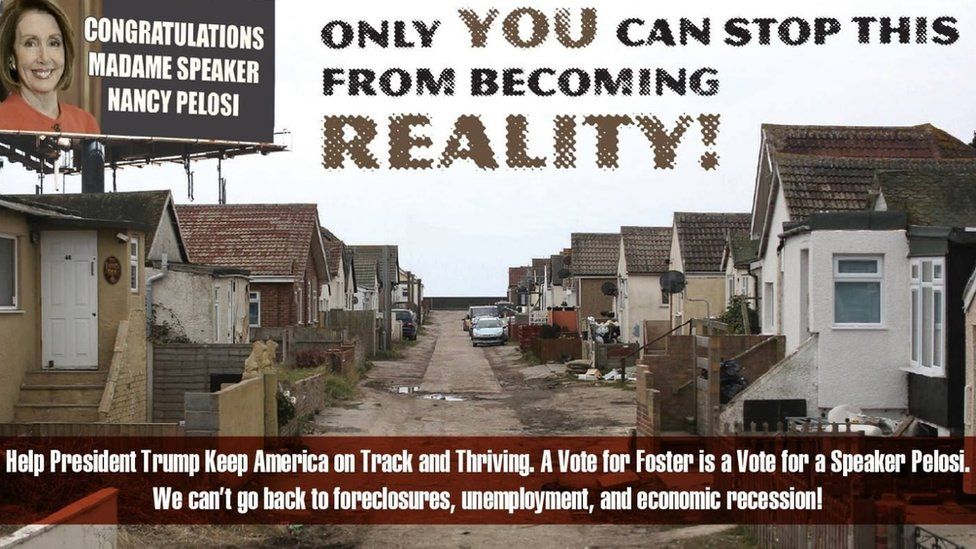

Further up the coast is Jaywick, named one of the most deprived places in the country in 2011, with more than half of working age residents receiving state benefits. Jaywick was again named England’s most deprived area on the Indices of Multiple Deprivation list in 2015 and will most likely feature again in 2020. It is internationally renowned, too. A view of Jaywick was used by a US Republican party politician and congressional candidate, Dr Nick Stella, in a political attack ad against Democrat opponents. ‘Only you can stop this from becoming a reality’, the slogan warned.

Jaywick was the location where Channel 4 recorded the controversial Benefits by the Sea reality television series. Critics accused the broadcaster of developing a new genre of ‘poverty porn’ that enabled middle class people to gawk at the deprived lives of those less fortunate, akin to some modern day freak show. However, you can imagine the Channel 4 film crew had spent much more time with the residents of Jaywick that any politician had at that time, or since.

In the drama, Brexit: The Uncivil War, Carswell is depicted as visiting Jaywick with Vote Leave chiefs, Matthew Elliott and Dominic Cummings. They arrive at a run-down estate in Jaywick and Carswell is depicted, with arguable accuracy, as saying: “I don’t know this place.” The actor playing Cummings cutely replies: “Well, it’s in your constituency.”

Multiple complex issues combine in Jaywick, but one notable problem is housing. Much of the housing in the area was built for holiday homes aimed at people coming from London for a break. It was never designed for year-round living. Grumblings abound among residents of a disinterested local council unwilling or unable to tackle the problems in housing and beyond. They are the truly left-behind, and so it is unsurprising that a vote for the status quo in the EU referendum was never going to appeal.

As time is tight on our visit, we don’t walk further on towards Jaywick and instead head back towards Clacton to explore the town. (I fully appreciate the contradiction of criticising politicians for declining to come to Jaywick, and then doing exactly the same myself.) As we head back along the winds-swept but pleasant beach walk, a woman with purple hair strolls past us, dragging two small dogs behind her that have become preoccupied with a much larger dog, who in turn appears somewhat reticent to engage with proceedings. On the sand a mother and her children pick up litter from the sand and put it into a bin bag. It’s clear this beach is well loved.

The sand is thick and inviting. A squat hut sits with the words ‘Beach Patrol’ written in red on the blue painted wood. The Essex coastline is one of the most protected in Britain due to the wildlife. It has the strongest level of European preservation under the European birds and habitat directives. Further on, a memorial marks the spot where Sir Winston Churchill, then the first lord of the Admiralty, made a forced landing in a naval seaplane in April 1914. If it had happened today, Sir Wintson could have availed himself of the offer of an unlimited breakfast for £4.69 at the Toby Carvery nearby while he waited for a rescue.

We walk back into town and see a rather dour looking Premier Inn hotel, which sits on the site where the house on 7 Marine Parade once was. This was home to my Great Great Great Uncle William Willis in the 1880s until his death in 1892. William Willis was a Master Mariner and Shipowner who was born in Wivenhoe but retired from a life at sea to Clacton-on-Sea and took on the role of Harbour Piermaster in the 1880s until his death. (Credit must go to the countless hours that my Dad spent in the archives of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich and the National Archives in Kew for this nugget of family history).

In front of the hotel sit some pretty landscaped gardens, each with a different theme, such as the Mediterranean Garden. A sign features a dog pointing in the style of Lord Kitchener with a message that says, ‘TENDRING NEEDS YOU: To bag it and bin it!’ Benches are everywhere, each with messages marking the passing of someone’s relative, loved one or friend. In one garden is a clearly well-tended memorial to PC Ian Andrew Dibell. In 2012 Clacton resident Trevor Marshall arrived home to find his neighbour, Peter Reeve, there to confront him. Reeve was armed with a gun. Marshall attempted to flee but Reeve shot at him and then pursued in a car. Marshall headed towards Redbridge road, where PC Dibell lived. He was off duty on that day, but upon seeing Reeve he dived in through his car window to seize the weapon. In doing so he was shot in the chest in a fatal wound. Reeve escaped, but his body was later found in a churchyard in Essex. He had shot himself. PC Dibell was given a guard of honour at his funeral and was later posthumously awarded the George Medal for gallantry, the first police officer to get the award for more than 20 years.

The sky above thickens with soupy clouds and it’s clear that rain is coming. We decide it’s time for lunch, and so head to Geo’s fish bar. A takeaway is at the front, and a restaurant at the back. A musty heat hits us upon entering. The décor is mostly based around brown melamine. It’s the kind of place with proper plates, bottles of vinegar on the tables and steaming mugs of tea. It’s cash only. I instantly love the place.

We sit down at a table and peruse the menu, while also eavesdropping on two couples nearby, average age of around 65, discussing the merits of different types of hearing aids. We order and not too long after arrives mountainous plates of cod and chips. The portions are huge – fish falling over the plate, chunky chips and a bucket of mushy peas. Bread is optional, but encouraged. We eat until it gets uncomfortable to go any further.

With a strong need to walk off about three pounds of solid food slowly digesting like a radioactive core in our stomachs, we head out to further explore the town. The last time I was in Clacton-on-Sea was more than 20 years ago. We find the specific spot where I posed for a photo in 1997. My messy thick curtained hair has reduced considerably over the years and the lines and wrinkles have deepened. I look at my previously fresh faced complexion and curse the passage of time. It is my fortieth birthday in a few days and I can now comfortably measure memories in decades.

Across the road is the Pink Palace Hotel, a passable take on a deco Miami hostelry complete with a vintage black American car parked outside. The rain that was threatened earlier has now arrived, so we head back towards town. An electrician argues with two men about wiring outside the Kassaba restaurant. “You can’t have wires exposed on the deck,” the electrician says. “Someone will kill themselves.” The other men don’t appear overly convinced by that argument. An amusement arcade fire truck ride rolls across the road, pushed by two workers hidden from view. It looks as though the ride has become sentient and made a break for freedom, but is now being pulled back into captivity. Go little fire truck, go.

We follow the enslaved ride on its journey back to Clacton Pier. Although work is being done on repairs it is still possible on this spring day to get onto the pier. As we enter the amusement arcade we’re hit with the usual wall of noise. Hundreds of machines compete in a bleeping contest, punctuated by chattering floods of coins, like pots and pans falling down a flight of stairs. Prizes are available for winning tickets, and you can see the promised bounty hanging from the ceiling. It’ll take a rather daunting 10,000 tickets to win a slow cooker. Winning 8,000 tickets seems somewhat more achievable to take home a fetching pedal bin. Both challenges appear to be utterly beyond us, particularly as our reaction speeds are still rather slowed by the still digesting mound of carbohydrate in our stomachs.

Instead, we leave the orchestra of victory behind and head outside onto the pier. The sea air whips across as we navigate the various attractions and amusements, most of which are closed for the winter. At the end is a rotunda café giving panoramic views out to sea. It’s virtually deserted on the wooden board pier, barring some men fishing at the far end inside glass walled enclosures, like bus stops, giving them some protection from the elements. Their fishing rods twitch in the air, but no one seems close to a catch. We stand and look out to sea, enjoying the moment and the silence.

Three months after my visit to Clacton, my employer, the consumer group Which?, would name Clacton-on-Sea as Britain’s worst seaside destination alongside Bognor Regis in West Sussex. Clacton gained a customer rating of only 47%, compared to 89% for Bamburgh in Northumberland and 81% for Southwold and Aldeburgh further up the coast from Clacton in Suffolk. Which? members surveyed gave Clacton just a solitary star for attractions, as well as peace and quiet. That rating possibly has basis but does seem rather harsh.

Clacton beach is well kept and inviting. Considering Clacton is only an hour from London, it seems strange that it doesn’t have the same pull as Brighton, with its pebble based beach lacking similar charms. While places such as Whitstable in Kent have reinvented themselves to appeal to holiday makers and younger people looking to escape London, it appears that Clacton is stuck in the past, frozen in time as the world around it changes. And in such circumstances it is always easy to look for who is to blame.

Exiting the pier, we head back towards town. It’s now late in the afternoon and the atmosphere seems notably tenser and more rowdy. As we walk back up West Avenue a pallid-skinned woman marches past with a twitching gait. Two men and a woman cackle loudly in the doorway of Peacocks clothes shop. “Yeah, well she can go fuck herself!” the woman bellows like she was calling out a food order for collection.

My Dad looks up at a Poundland store, ‘didn’t they go bust?” he asks. I blow my cheeks out and decide that it’s time for a drink.

We head to the Warwick Arms pub, surrounded by a bleak car park, like a moat made of concrete and weeds. The pub itself is a converted semi-detached house, with paving slabs of varying pastel colours in front from the golden age of ‘crazy paving’. Advertising boards outside promote the B&B accommodation and a function room for hire. It’s so dark inside that we aren’t sure if it is actually open. Undeterred, we try the door and venture inside. It’s 3pm and there’s a gaggle of drinkers at the bar. A few seem already several drinks into the session.

I motion my Dad to find a seat in one of the pinky-red velour booths, and then get us both a drink. All around the walls are mock Tudor beams. A couple sits at the bar. The man drinks a pint of lager and she has a sugary alcopop of some description. I figure they’re probably in their late 60s. A younger man talks to them, gesticulating with his pint to punctuate certain points. “So he needs to go into assisted living and the council says no,” he explains to a few ‘oohs’, ‘ahs’, and shaken heads. “So, I says, ‘look, you just bought a £3m building in town, how can you say no?’ Well, the bloke don’t know what to say to that, does he.”

The couple ‘tsk’ in agreement. A giant of a man walks in. He must be well over six feet tall and easily more than 20 stone. He walks with a cane. You could imagine he was called Frank or Dave or John, with either the prefix ‘big’ or ‘little’ depending on his friends’ penchant for irony. They continue to lament the alleged ineptness of the local council, occasionally look over with bemused indifference at my Dad and I sat in a booth near the window. I wonder if we would be pulled into the conversation or possibly have our heads kicked in. In the end neither outcome occured and we just finish our drinks and head back out into the afternoon drizzle.

As is often the case with these trips, I end up in a Wetherspoons. It is, after all, hard to resist the siren song of cheap beer and sticky carpets. In the Moon and Stars, we get another drink and sit down on one of the high tables. A couple sat near the window canoodle each other, periodically slugging on large bottles of Hooch or going out for a cigarette break. The latest Brexit developments are displayed on the flatscreen TV on the wall. A man idly watches with a grim-faced expression. I look down at my pint glass. The golden liquid inside illuminates a marketing slogan on it. It says; ‘TO THE BITTER END.’