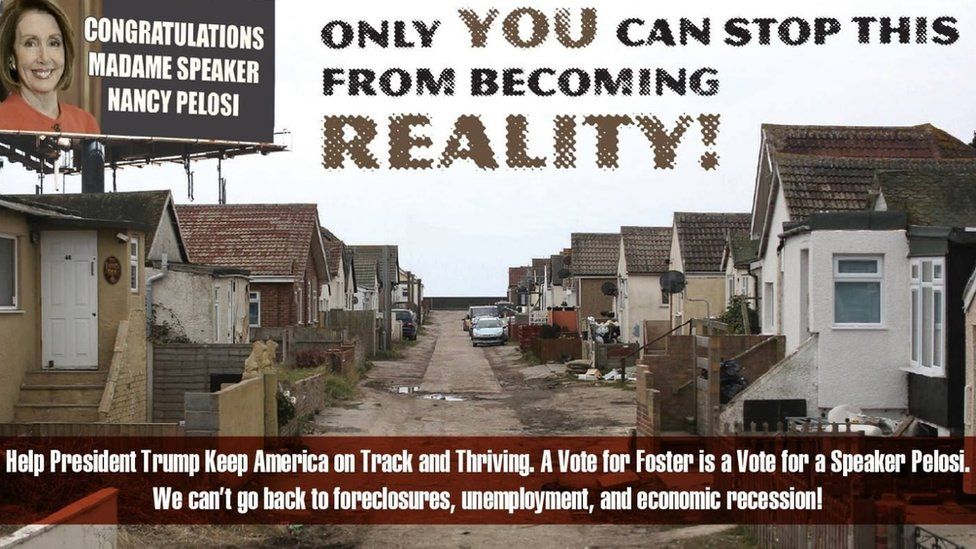

The End of the Line is a 10-part travelogue journey to some of the highest Remain and Leave areas in the United Kingdom’s 2016 Referendum on EU membership. It was written over two years from 2018 to 2020, before Coronavirus made Brexit seem like a spot of man flu.

Scarborough voted 62% Leave in the EU Referendum

Originally written in March 2019

There’s a certain romance to an English seaside town. Rather than florid emotional poetry of sunsets and summer seductions, however, it is romance written firmly in study prose. It’s a whole world of emotional drama restrained behind a very British façade. A somewhat buttoned up and regimented sense of fun that has a charm all of its own. And few places epitomise that so perfectly as Scarbados, the self-named, ‘Queen of the Coast’. Kiss me quick, squeeze me slowly: but always remember, we’re British.

Before heading to Scarborough, I have a few other stops to make on a short Northern tour. My first journey is from Kings Cross to Leeds in order to catch a connection to Skipton, where a friend of mine had recently moved. I’m booked on the 1.33pm train but it’s cancelled due to a member of the train crew seemingly not turning up for work. That action has resulted in three trains worth of people cramming onto just one. I stand for the entire journey, boxed into a space where the carriages connect so small that even Houdini would fear lasting back pain. My spine slowly curves from leaning up under the arch and my ears ring from the squeaking creak of the linkage between the carriages.

The windows of the train carriage soon steam up as the temperature of crushed bodies increases. When the train reaches a station a blessed blast of cold air rushes in, but it’s merely a temporary relief as more people immediately replace the ones that have just got off. I glance over and see a pregnant woman also standing, with no one appearing keen or even able to give her a seat. She’s just too far away for me to offer her help. Not that there is much I could actually do. It’s 2pm in the afternoon on a weekday, hardly the peak time of rush hour.

The guard apologises over the public address system for the overcrowding and then optimistically suggests that a trolley cart of light refreshments will be making its way down the packed train. You imagine this will involve us ferrying the cart on our shoulders like Paul Hogan surfing the New York subway crowd to reuinte with Linda Kozlowski at the end of Crocodile Dundee. In the end, it never appears. Instead, I stand close to the toilets and try to avoid inhaling the occasional waft of stale urine as the doors open and close, open and close. The guard advises us that we could apply for compensation, so I spend the time imagining what I would buy with the likely £5 of redress coming my way. How cheap are chiropractors, I wonder? Eventually we arrive into Leeds and I tumble out of the packed sweat box, battered bruised and £70-odd quid lighter for the experience.

On the train to Skipton I manage to get an actual seat and it feels like a lottery win. The pretty Yorkshire town of Skipton is in the voting district of Craven, which plumped to leave the European Union at 52.8%. By contrast nearby Leeds just narrowly voted to Remain, at 50.3%. Leeds is a rarity on that score, as the vast majority of the North of England voted out, including my home town of Sheffield, at 51%. In the spring evening in Skipton the starlings flock in the sky, swirling in quite beautiful sweeps of black and raining down faeces like the US Air Force carpet bombing the Taliban. The evening ventures towards blue, then pitch dark as beer, curry and then sleep ease away the strains of a day spent travelling by train in Britain.

In the morning I board the 10.17am train back to Leeds, in order to get a connection over to Sheffield to see my Sister. A group of five women in their 50s and 60s get on just behind me. I ascertain that it is one of their birthdays and they are off on a day out in Leeds. The train hadn’t even left the station before the Prosecco cork popped to happy cheers.

“It’s organic,” one of the woman says as she pours the booze into waiting glasses.

“Where’s it from?” another woman asks.

“Sainsbury’s,” comes the answer. They all laugh.

One of the women reaches in her bag and retrieves cans with mixed cocktails in them.

“Drink up,” she says. “I ain’t carrying these round all day”.

As we reach Leeds around 40 minutes later, one of the party stands up, and wobbles on her feet. “I’d better have a coffee or I am going to pass out,” she warns.

As the party tumbles out onto the platform, a young woman observes them as they pass with a head tilted smile. “I hope I am like that when I’m 60,” she says to a friend.

On the connection from Leeds to Sheffield I log on to the free wi-fi. This always involves some odious request for personal data and so I have become quite creative at developing online personas. I like to think that somewhere a marketing person is sat staring at a list of names, trying to think what promotional messages would suit Tony’s Technicolour Underpants, The Lord of Death or Big John’s Love Sack. Outside the window whizzes past a forest of caravans just outside Wath Upon Dearne. I settle in for the journey to Sheffield.

“I am so sick of hearing about Brexit,” my Sister says after she picks me up from Sheffield station in her cream Fiat. She’s booked a holiday for 1 April, 2019 in The Netherlands. When I asked why, she replies: “It was cheap”. I counter that by suggesting it was possibly cheap because you’ll need a visa if we crash out of the European Union without a deal. “So will I need a visa or what?” my Sister asks. I shrug and say, “No idea.” She merely harrumphes and we continue on the car journey in silence.

Midday in Sheffield, and it’s raining. It continues to rain for the entire day and into the evening. I get thoroughly drenched and dry out on multiple occasions to the point where I no doubt smell like a wet dog. Still, the beer-curry-sleep combination again does its magic.

To the seaside, not beyond

The following day the rain mercifully gives way to bright sunshine and clear skies. Perfect weather for a trip to the seaside. The journey from Sheffield to Scarborough goes via York. Alongside Leeds, York also voted to Remain in the European Union, at 58%. It was unusual in that regard, as being both a place with a great sense of history, yet also a seeming desire to remain in a globalist future. But although its station is a handsome sight, it isn’t the end of the line, so I must move on. Rules is rules, after all.

My Mum was born in York. My Grandad died here. Grandad Ralph got dementia in his later life and I used to tell with puzzlement how he once claimed he had a baby growing in his leg. Now, I look back and realise how terrifying that must have been for him. To know everything and nothing at the same time: at once lucid and also absent. My Mum would later die of Multiple Systems Atrophe, or MSA, a condition that keeps you alive and conscious as it gradually robs your body of motor skills. Trying to decide which is preferable as a way out is a bit like considering which form of Brexit you’d prefer best.

I board a train to Scarborough. It rolls out of the station, giving a trackside view of the large houses of York, surrounding by the fortified city walls. The sunshine pours down and the sky is a powder blue. The light beams down onto the fields, illuminating them in a vibrant green. I try to avoid looking at a man vigorously picking his nose in the seat across from me. It’s like he is rooting down the back of the sofa in search of his car keys. The countryside goes on and on. The ruins of St Mary’s Abbey appear on the left hand side of the train. Manor house lord it over expansive grounds.

A man in a cap holds a conversation on speaker phone a few rows down. He holds the phone close to his face and bellows into it, with the respondent dutifully bellowing back. I wonder to myself why this is still not a crime with devastating punishments for non-compliance. Mercifully he gets off at Malton. The hills keep on rolling. Hulking shire horses stand idly in a field eating patches of grass. I relax back into my seat, but then sigh as someone starts playing music on their smartphone without headphones.

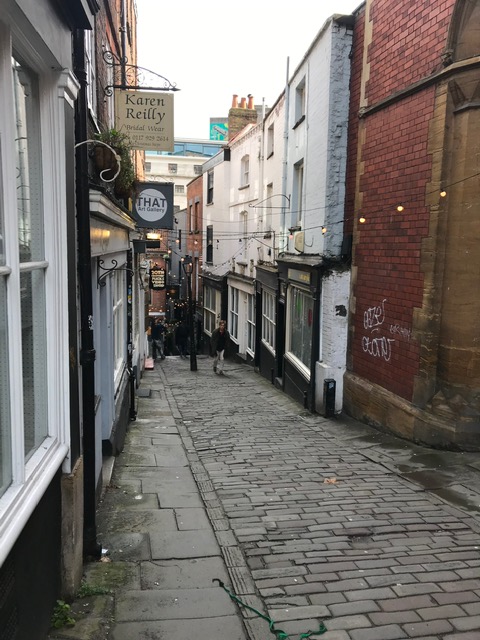

Seamer comes next – a bleak station surrounding by scrub brush and intimidating metal fencing. Then, we roll into Scarborough. Just as in Hastings, while it may seem strange to come to a seaside town in the winter, I know from living in Brighton that you only see the real character of a tourist town or city when it is out of season. Only then do you glimpse what it’s like to live here when the hoards aren’t descending and the attractions aren’t in full flow. You have to come to these places when the music has stopped and when reality has resumed, to see their real character.

This isn’t my first visit to Scarborough. In fact I have been here numerous times. I used to come here for day trips and holidays, along with Filey, Whitby and Bridlington further up the coast. Saltburn by the Sea is much further up, alongside Redcar and then arriving in Middlesbrough. Apart from Newcastle Upon Tyne, the majority of the North East of England voted out of the European Union. Scarborough backed leave by 62%, and this was despite local Tory MP Robert Goodwill campaigning for Remain. As Scarborough Borough Council’s UKIP leader, Cllr Sam Cross, cutely put it at the time of the vote: “This looks like a fantastic result for the ordinary folk.” Mr Goodwill would later be among the group of 202 MPs who backed Theresa May’s EU withdrawal deal, which was rejected by a record 432 MPs. Never take a betting tip from this man.

I exit the train and walk into town, passing a man with a sleeping bag around his shoulders and a two litre bottle of cheap Frosty Jacks cider in his hand. More homeless huddle up ahead to ward off the cold. Around 320,000 people were recorded as homeless in Britain in 2018, up 4% on the previous year’s figures, according to data from housing charity Shelter. Combined, that group of people would be bigger by population than the UK’s 15th largest city. Plus, these figures only included individuals who were in contact with local authorities or in hostels, so the real figure could be much higher. People are struggling, and that doesn’t always end just because someone eventually does get a roof over their heads.

Scarborough developed into a spa town in the 17th century following the discovery of a spring at the bottom of the cliffs. People flocked to the town to drink the water that they thought would cure all sorts of diseases. This was given some medical credence in the 18th century when doctors advised people that bathing in seawater was good for their health. Towns like Scarborough and Brighton soon developed into desirable resorts, and destinations in their own right. Scarborough’s population increased by almost five times over the 19th century as the tourism industry grew. Although Scarborough remained a busy fishing port, gradually its ship building industry started to decline. The resort grew in the 1900s but as with most seaside locations in Britain, it hit the wall in the 1960s with the rise of cheap package tours abroad. Just like Skegness and Clacton-on-Sea it has struggled to recover ever since.

The average salary in Scarborough in 2016 was just £19,925, compared to the national average of £28,442, according to data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Permanent jobs are hard to come by, with most work residing in low paid and seasonal tourism positions. Scarborough also has an aging population. According to NHS data for 2015, Scarborough had 13% of the population aged 65-74 and 7.6% aged 75-84, that is 3.6% and 2.4% higher than the national average for England respectively. By contrast the town has 33.2% of the population aged 15 to 44, 6.9% below the national England average.

The UK population generally is getting older. Between 2005/06 and 2014/16, the number of people aged 65 or over grew by 21%, while people aged over 85 increased by 31.3%. It is projected that the population over 65 will grow by 48.5% by 2036 and people over 85 will increase by 113.9%. The demand for care for complex, long-term conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer’s is expected to grow at the same time and that in turn is expected to exacerbate socioeconomic disparity in terms of access. In short, a grey storm is coming and it could hit Scarborborough hard.

On this crisp spring day, I walk over to The Helaina where I am staying that evening. It is a presentable B&B right on the front overlooking the North Bay. Looking out to sea, the view sweeps from the colourful chalet beach huts on the left all the way across to Scarborough Castle on the right. Further down the cliffs kids play on a playground and two boys kick a football around a small pitch. Dogs amble on ahead of their owners and people sit on benches looking out at the waves.

A small white ball flies past me down a slope leading to the edge of a steep cliff as I sit and take notes in my book. A man approaches, coaxing his small dog with him who seems reluctant to retrieve the ball that she was clearly meant to catch. The man tries to persuade her but eventually just picks the animal up and drops her just over the edge to retrieve the ball. “There,” he says as the slightly shell-shocked dog returns with the ball. “Wasn’t hard, was it.”

Mel checks me into my room. Or rather, doesn’t. “Room’s not ready yet, love. Sorry, we were slammed last night. So busy!” I leave my bag at reception and comment on the chilly weather.

“I like it like this,” Mel replies. “Sunny and cold – can’t beat it!”

Giving time for my room to be prepared, I head back out towards the Castle positioned on the promontory rock looking out over the North Sea. A fortification has stood here for nearly 3,000 years, but the main castle tower was built in the 12th century as the centrepiece of Henry II’s castle. It was one of England’s most important royal fortresses at the time. Dropping down the winding paths I reach Marine Drive and the Teapot Kiosk. Sunday bikers are out in force. They gather around outside tables in leathers or high-tech romper suits, trying to look manly as they tuck into tea and slices of cake. Luna Park is closed up for refurbishment, but no doubt provides a heady mix of fun and health and safety concerns when it is open. Ahead is a working harbour: salty ropes are coiled in wet piles, lobster pots are stacked in rows and workmanlike boats sit waiting for tomorrow’s catch.

Surprisingly given it is a chilly Sunday in March, the South Bay harbour bustles with tourists. Families and couples amble down the front, dipping into shops for fish and chips, sugary snacks or an afternoon pint. Above them hovers an airborne army ready to relieve them of their purchases. The seagulls in Scarborough are aggressive, so aggressive that warnings line the front advising people to guard their food against the threat, along with the Twitter hashtag #yourfoodisnottheirfood.

“Shut up, you,” a woman chastises a squawking gull as she walks past the bird.

Heading down Sandside leads onto Foreshore Road. On the thick, inviting sand people play games, take rides on donkeys and try to get a tan from the occasional flashes of sunshine. A man wearing a leather deerstalker rather sheepishly runs a metal detector down the shoreline in the hope of finding something valuable. The amusement arcades rattle and hum with life inside. I dip into Coney Island and am immediately hit with a wall of noise – like a brightly coloured mental breakdown. I play a few games and then, over fear of impending tinnitus, head back out again.

Further down the front leads to the Grade II* listed Scarborough Spa. I can recall coming here as a child. It feels vivid, like it was only yesterday when I would visit the little row of shops, always obsessing over some plastic toy or trinket. We’d get ice creams and my parents would enjoy a few moments of peace while they had a cup of tea. Just like many people, I grew up with these sorts of holidays, which would now odiously be called ‘staycations’. The Spa is now a theatre and entertainment venue, with a beautiful outdoor performance area bedecked with glass windows and a rotunda with views out to the sea.

Above the Spa is the Grand hotel, which has a lot of history (apparently, it was built on the same site as a house where Anne Bronte died) but has clearly lost its way. Built in 1863 to cater to wealthy visitors, the hotel is under the Britannia Group, named by Which? magazine in 2018 and 2019 as the worst hotel chain in the UK (disclaimer, Which? is also my employer). It had more than 2,800 ‘terrible’ reviews on TripAdvisor, including tales of dirty and decaying rooms, disinterested staff and tasteless food. As I walk past I notice that the door apparently leading to the Empress Suite has one of the panes broken and hastily covered with a slab of chipboard. Come in, your Imperial Majesty, just avoid the needles as you go.

Glad that I had not booked that particular delight for this evening, I instead head back to The Helaina to check in. After getting refreshed in the small but very comfortable room, I head back out. Instead of retracing my steps I go the other way towards the front. It’s starting to get late in the afternoon and the shopping arcades are now dead. Rubbish floats on the wind like tumble weed as bored-looking kids gather searching for something to do. Old people congregate around Greggs drinking tea to ward off the cold. It’s rather a bleak scene so I go back down to the South Bay front.

As I reach the Spa, the skies begin to dim in preparation for sunset. Surfers are in the sea braving the cold for the robust waves rolling in. Most are wrapped up extensively in wet suits. The majority of day trippers have now gone and the front has the feel of a party starting to wind down. There is a sleepy lull in the atmosphere, an almost soporific calm as people ratchet down from their various highs. I look up at the skies as the first droplets of rain start to fall. So, I venture into The Golden Ball pub for a drink.

As I sit down with my pint in the rather funereal upstairs bar area, the now heavy rain starts to batter the outside window. Three couples are in the room: the oldest natter away to each other, the youngest stare intently at their phones, only sparking conversation when one runs out of battery. After the rain stops I swap venues for the Scarborough Flyer – a huge pub that really should be a Wetherspoons, but oddly isn’t. As I get a drink at the bar a man wearing a St Patrick’s Day oversized hat and appearing to have been drinking for quite some time, eyes me sideways.

“You look shifty,” he comments to me. I laugh nervously, but he doesn’t. I move as un-shiftily as I can a little bit further down the bar. Later, I see him being thrown out of the pub and the hat, which it turned out wasn’t even his, relinquished from him.

A group sat near me talk about how people fetishize living by the sea. One of their friends wants to come back home to Scarborough after living in London, and it sparks a debate.

“She don’t need to be here. Stay in London,” one says.

“I can’t stand it down south,” another counters. “I have done it a few times and I find it fucking horrendous.”

“I like London but after a couple of days I am ready to go back. It’s the rat race, right. But I don’t think Georgie would be happier coming up here. She just thinks she would be.”

“She’s 39 and chasing this image of what she think will make her happy. But she needs to stop chasing. You should know by now what makes you happy. I see the fashion life and it is fun and all, but then soon you are like, ‘take me back to the slow mundane life by the coast. Take me home’.”

I end the evening in Tricolos, an Italian restaurant whose décor is akin to the set of a local theatre company’s take on Merchant of Venice. I dine alone on a pretty serviceable calzone. It is always a slightly odd experience dining alone, but I encourage everyone to try it. There is something about enjoying your own company that feels a positive, life-affirming experience. Of course, there’s also a high possibility that other diners just look at me and think, “Well, that guy looks pretty shifty.”

Freddie Gilroy looks out to sea

I love the atmosphere at a B&B breakfast in England. Couples, groups and singletons emerge like overly polite meerkats from the privacy of their own rooms, forced to interact – however briefly – at the collective wateringhole in the need of sustenance. The breakfast at The Helania is hearty and everyone seems satisfied. After finishing up I check out and have a chat with Mel again. She only came to Scarborough just over three years ago. The B&B is closed over the cold winter months of November and December, but the start of 2019 had already been busy, with guests staying for a weekend or longer visits. There are even residential apartments where people working on the fishing boats reside for a month or longer.

“It’s been busy, yeah,” Mel says as she hands me a bill. “More so as people are worried about the terrorism.”

“The terrorism?” I ask, somewhat concerned.

“Yeah, you know. Not so much here, as it is quiet, but in London,” she says. “People are worried to go there. They want somewhere quieter. Then again, if all you thought about was that sort of thing, then you probably wouldn’t go anywhere!”

She smiles broadly, before making her excuses to answer the endlessly ringing telephone.

The morning is hazy, but also bright and sunny. The view of North Bay outside the B&B is truly stunning. The waves roll in thick swells and the sea sparkles in the sunlight. This time, I set out walking down to the North Bay promenade. People are out walking in the clear air. Dogs gather on the beach like a canine coffee morning, frolicking and catching up on important dog matters. Tired young parents bereft of sleep push sleeping infants, hoping that the chilly air would keep them asleep and, in turn, themselves awake.

On a giant bench is a towering statue entitled Freddie Gilroy and the Belsen Stragglers. It depicts a local man and former miner who was one of the first Allied soldiers to enter the notorious Belsen concentration camp when it was liberated in World War II on 15 April 1945. What he saw there would stay with him for the rest of his life: the most extreme form of human cruelty given full lease to roam. Gilroy was hit by the smell of rotting bodies, and of those still alive, almost half were as close to death as a human can get.

Gilroy would spend his 24th birthday at the camp, and in a later interview with a newspaper in the 1980s, he explained how he cried on every birthday since that day. He died of cancer in November 2008. Freddie was an ordinary man who witnessed extraordinary things. The statue was eventually made a permanent addition to Scarborough’s seafront after it was purchased for £50,000 and gifted to the city by pensioner Maureen Robinson. Mrs Robinson bought the sculpture as a thank you to Scarborough for all the happy years she had spent in the town. I get a little choked at this moment, but then a man walks past wearing a jumper with the slogan, ‘I believe in the Loch Ness Monster’, and that brings me firmly back to reality.

Further up from the statue is a rainbow swathe of brightly coloured beach chalets. Many are named after types of birds, such as kingfisher, grouse and lapwing. Pensioners sit on chairs outside sunning themselves or chatting with friends. I stop off in the Watermark café for a coffee. The café is filled with elderly people making a laboured effort to either stand up or sit back down again. A woman in her 70s sits down next to me and spends 15 minutes moving things around the counter top, like an elderly version of block puzzle game Tetris. Her friend arrives and does exactly the same thing. Her dog barks intermittently but she does nothing about it. Time to leave.

Walking onwards leads to the Sea Life Sanctuary, a series of tented buildings housing an aquarium and mini golf centre. I loop around it and on towards Scalby Mills. A small train platform sits here as the end of the line, with miniature steam trains going from Peasham Park and back again on the weekends. Up on a short cliff walk you get a staggering view across the bay. It really is a beautiful sight. Behind are the Scarborough suburbs. On Scalby Mills Road sit modest but well preened houses, with manicured gardens and family SUV cars parked up in the driveways. It is the kind of road where it is the done-thing to name your house. It’s always a fine balance between the grand and the modest, the poetic and the practical – The Headlands, Greenacre, Lilywhite. Why doesn’t anybody go for something a bit spicier, I wonder? Maybe, ‘War Bastard’, ‘The Fuck Bunker’ or ‘Chemical Weapons Testing Facility’. See how that goes down with the Nimbys.

I walk back towards town, making a beeline for the old Scarborough Prison on Dean Street. The Grade II listed building was opened in 1866, but only lasted 12 years before closing in 1878. In that time it accommodated only around 50 prisoners and it is believed that one of those managed to escape by scraping away unset mortar and removing the bricks. The site is now used by Scarborough Borough Council for storage.

Just up the road is Scarborough Workhouse, a particularly cruel institution from British history. With origins dating back to the Poor Law Act of 1838, the workhouse had conditions deliberately intended to be harsh and unforgiving to deter able-bodied people from looking for a free accommodation. In many ways this was the first marker in a long held belief that you could batter and beat infirm, broken and damaged people into being contributory citizens. The ‘pull thyself up by thy bootstraps’ form of welfare still sustains to this day in the form of Universal Credit.

Back on the front, the sunny weather has ensured it is lightly busy for a Monday afternoon. Day trippers dip in and out of the amusements and food outlets. I opt for Winking Willy’s fish and chip shop as my final stop, ordering fish and chips with slices of bread and butter, because, well, there just aren’t enough carbs in this meal already. I am upsold to have curry sauce with my chips, but while tempting, I decline on this occasion. When I first moved to Brighton and asked for curry sauce with my chips the man behind the counter looked at me like I had just asked him to lather the potato with boot polish. “Gravy then?” I followed up, somewhat optimistically. Maybe there is no place like home.